The Rebirth of Luna

Luna’s been rebirthing. You’d think she would have learned!

Luna’s about 7 years old. For an oven built as a prototype, that’s getting on. She’s had a robust, quite eventful life so far. She’s lived in four locations, as well as a short stint living ‘on the road’, as the centrepiece to my first travelling bakery and classroom. She was designed to be a mobile, high volume wood fired oven. She was meant to be light, heat up quickly, and be able to bake 300 or more perfect loaves of bread in the space of a market - which would be around eight hours.

For this task, she was a complete failure. The entire mobile bakery enterprise had a number of flaws, as it turned out. I may well have covered these, and the mobile bakery, in a previous blog post; I can’t remember. Anyway, that’s not what this post is about.

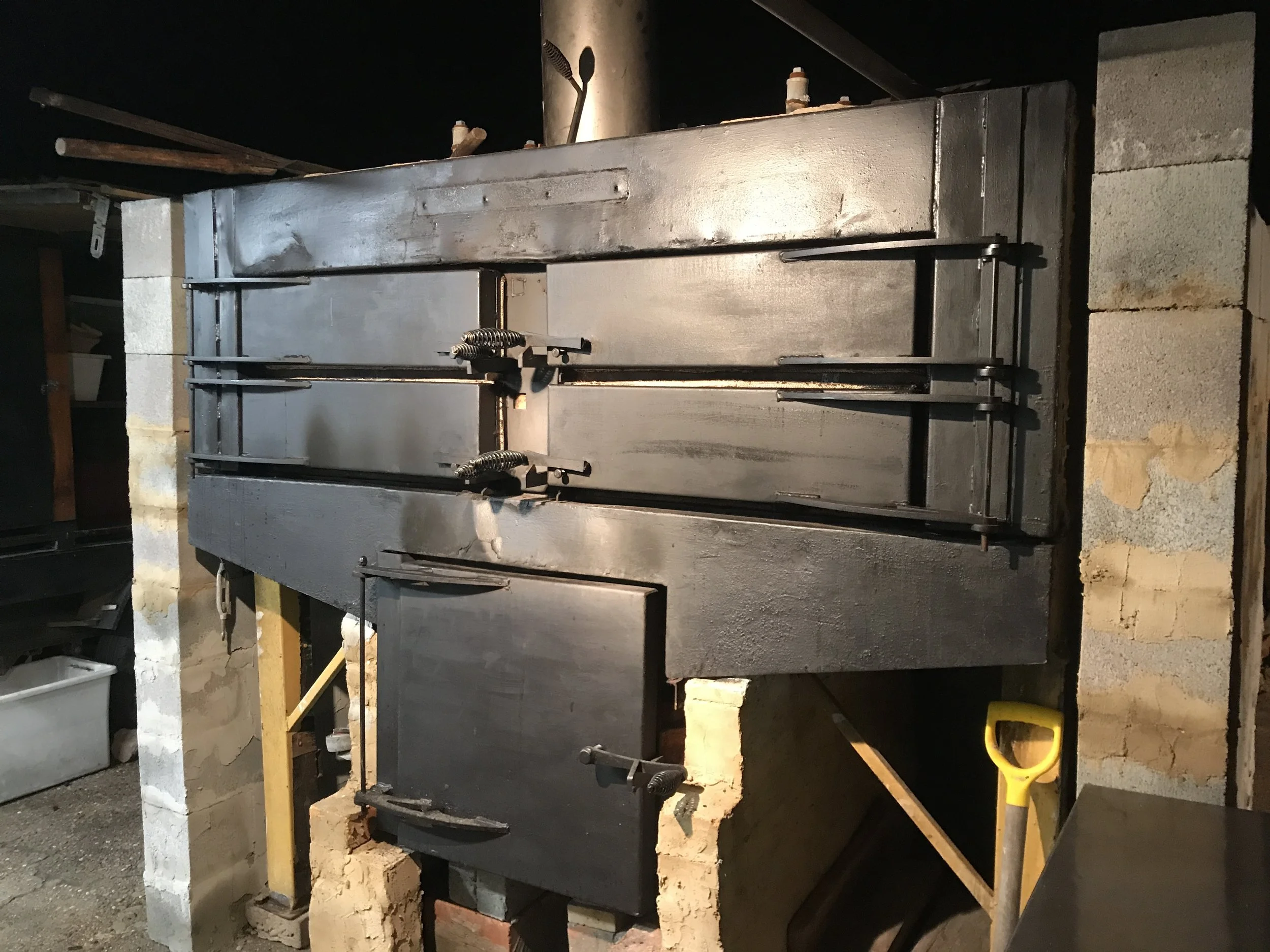

That’s Luna’s bush hideaway. She’s in the box…

Luna found her place as a stationary oven. She lived on a fixed site, still on the mobile bakery trailer, at a bush hideaway in Ellalong, where she performed the weekly baking duties for local Saturday markets with incredible finesse. I knew the difference Luna made - a kind of crust that only a brick oven can give you.

She was always a bit tricky to work with - she liked to be pre heated for a good 5 hours before she would really begin to sing, for example. She had some hot spots (which became completely ‘worked around’, as one does with any old bakery oven), and she needed a major clean out and overhaul every year, or she would block up (and actually melt) in parts. I had to rebuild the firebox a couple of times, and used a crowbar to open up a pathway for flue gases when it fatigued after about 5 years use.

I learned the hard way with Luna, every time, but after each rebuild she returned to work, better than ever. She was, for many years, a ‘work in progress’. She eventually became an excellent oven, capable of baking an average of 30 average sized full sourdogh loaves an hour - provided I was on my game - and more if someone was helping me. She did her job as a test bed and we improved our Aromatic Embers ovens as a result.

When the first Bush Bakery at Ellalong came to an end, I packed Luna up in the trailer, took out her bricks, and parked her in a nearby paddock, where she lived for a few months. I towed her here to the farm, and she was parked again for a few more months. We removed her from the trailer after the Tour Down South, and a boilermaker began the task of refurbishing her, with design modifications we had now applied to some of our other ovens.

Luna was my third prototype. I was the test pilot and outside design consultant. Actually, I became the crash test dummy more often than not. The first two prototypes, both named Bertha, turned out to be absolute pigs of ovens, but pigs which were made to sing for their supper nonetheless, thanks to my need to bake decent bread.

Bertha 1 in Cafe mode. Note bricked plate warmer on top!

Luna was different. We really thought about Luna - all our mistakes taught us what NOT to do. So Luna was a decent oven from the getgo - but she developed some long term issues. That’s why I was always working on her - she took a fair bit of tweaking to make her really sing, I can tell you! So when I left her in the boilermaker’s capable hands, I gave him my wish list - or at least half of it. I knew I’d be doing the other half myself.

This time I wanted to make the flame generated from the fire really stretch, so that it could do the job of heating more cleanly, quickly and efficiently. We needed to get the bottom decks more even too. Back in the day, the area above the firebox was always the hottest part of the deck. It was so hot that I had to set loaves to one side so they didn’t burn.

The boilermaker takes Luna apart with the tynes of a tractor.

Stretching the flame in Luna’s firebox.

The top decks have always relatively slow, so we set out to improve the heat here at same time.

The boilermaker built a more sophisticated and heavy duty baffle system, based on my ideas. He made the baffle itself more angled so that flame was siphoned off better when it runs against it from the firebox. I later bricked the inside of the firebox to further enhance the ‘flamethrower effect’. He rebuilt the firebox to include more brick than before. He also incorporated a whole series of cleaning access tubes to the roof of the oven, so that the area nearest the flue could be cleaned - an issue which had reared its ugly head a couple of times in Luna’s life already.

I’m hoping the changes to the flue system will eliminate the problem of soot build up altogether. I’m fully aware that I may simply be experiencing a case of wishful thinking here. Every designer wants their latest and greatest innovation to work - we always wear rose coloured glasses, to a certain extent. Sometimes, though, it pays to take out insurance. If there was still a build up of soot, despite our new modifications, at least I can now clean it out more easily than in the past.

Luna’s cleaning tubes before they get bricked and mortared.

All this work took many months. Luna was positioned in the middle of a paddock full of farm equipment. When the boilermaker was on the farm, he’d carry Luna’s bits over to the shed on the tines of the old tractor. He’d weld and angle grind and rivet for hours on end. From time to time I’d ‘lackey’ for him - just as I did when Luna was fabricated here on the farm years ago. Only then, as I remember it, I was on crutches. That’s a whole other story. Not this time - I walk pretty well these days.

More heavy duty thermal mass is added before putting Luna back together.

As the work on Luna slowly got done, a bit here and a bit there, the dairy shed also got finished - in much the same manner. A few weeks ago we carried Luna’s 2 finished pieces over to the dairy shed on the tractor, and we put her back together for the first time in a year. Then we positioned her outside the new school classroom and bakery, where she will live for quite a while, I hope.

Luna 2 showing inner layer of brickwork. This will be wrapped with besser brick.

I’ve been bricking her up, inside and out, for the past two weeks or so. It’s slow, heavy work, as a great deal of the brick is in really hard to get at places - inside baking chambers, for example. These baking chambers are only 16 cm high and a metre deep. One slides the bricks in on the end of a metal peel, and manipulates them as best as one can from a metre away. Around the baking chambers there are two layers of brick, and another layer on the top of them. Getting the bricks in place involves climbing up a ladder with brick or bricks in hand, keeping a fresh mortar on the go all the while, for maybe a couple of hundred climbs. Each brick weighs between 2 and 5 kg, and so far I’ve put roughly 500 bricks in and through and around the oven, as well as another couple of hundred inside the baffles, which we did before she was put back together. I’ve only done enough, at the time of writing this, to fire the oven up and make it work.

First layer of brickwork done. The oven is functional here, though nowhere near thermally efficient.

All this extra thermal mass and insulation will become necessary when Luna goes into production mode for the ‘Steady State Bakery’. It will operate as a heat sink, as well as a kind of heat mirror; the thick walls of brick should hold heat for days. Luna will become a super efficient oven.

i was inspired in my design for Luna by spending time at Harcourt Historic Bakery with Jodi and Dave when I did the Tour Down South last year. Their oven is capable of holding high temperatures for days after firing, as it has some 72 tonnes of brick around it. It’s an incredible piece of kit for a 100 year old oven. Dave manages to keep it hot with very little timber each day.

My version only will have maybe four or five tonnes of brick when it’s finished. The principle is similar to the oven in Harcourt though - get the brick hot, and then once it’s hot, keep it there for as long as possible. I’ll be looking for new bakery customers very soon, that’s for sure!

Next layer done. Still have to complete the outer wrapping, add more mass to the roof, and fill the besser bricks with rubble and sand.

Upon firing her up after putting her in place here, I saw that Luna was really a serious piece of flame art now. The firebox works a treat, blasting flame a good few feet each side, in sheets, spread out right under the two baking decks. It takes the oven from cold to baking temperature in just 3 hours, but will do it substantially quicker when it is fired each day or two, as it will retain a lot of heat.

Just a teensie fire here. When I fully blaze the fire, it’s too hot for my camera!

At the time of writing I’m about two thirds of the way through the brickwork. There is an ‘inner outer’ layer of brick around the baking chamber, and another around the firebox. There are two layers on top, with two more layers of grog based on mortar and recycled crushed concrete. There will be another layer of brick and mortar on top as well. There is a layer of besser brick surrounding the three sides, and I’m currently filling these with rubble, glass and sand to add thermal mass, as well as to use up everything I can from a demolished brick wall I was given. I’m going to fill a void between the inner and outer layers with insulation board.

My experience so far has been a bit different to what the world of oven builders has been telling me. One commonly held belief is that insulation like ceramic blanket or rockwool or ceramic board will ‘reflect’ heat back into the structure. While this is possible, there needs to be an outer layer of brick or thick mortar wrapping up the blanket in addition to the blanket itself for any reflection effect to occur. The blanket will eventually dissipate its stored heat in both directions - back in and out. If you wrap your blanket in brick on both sides, the blanket still fills with heat, but it slowly dissipates the stored heat back into thermal mass surrounding it. If you don’t wrap your insular material in thermal mass, you will ultimately allow 50% of the stored heat run out into the atmosphere. In addition, your insular material will actually be absorbing heat from the bricks next to it, contributing to a slower heat up of the oven itself. I learned this with Bertha 2, which took over 18 hours to heat from cold, and really only started to get useful after the second bake for the week. Needless to say, once I figured out our insulation mistake, I got to pull her apart and replace the insulation with brick, and this sped her heating time up by many hours.

The advantage of brick is that while it absorbs heat, it also reflects heat. If you sit beside a brick wall in the sun, you will experience how brick reflects heat. When it becomes ‘soaked’ with heat, it then becomes a heat source - it actually ‘radiates’. So you get reflection, absorption and dissipation (radiation) of heat, in that order. Brick, as a material to work with storing heat, becomes more efficient over time.

One uses ones loaf to make a decent loaf. Or so they say…

So far I’ve used the oven for my standard bakes, and have kept the oven warm over multiple days doing various tasks - slow roasting on one day and baking pizza on another. Luna can hold baking temperature without fire for a couple of hours at the moment. In fact, the top decks increase in temperature for the first six hours of firing, and continue to increase without fire for the next three hours. On some nights I have finished the bake and checked the baking chambers about 10 hours later, and they still held over 120 C. I think I can improve on this by a significant amount by just beefing up the thermal mass and adding strategic insulation in some places.

I’ve done the big stuff, now I will do the little things. Watch this space.

If you would like to experience Luna first hand, I run workshops for the general public each month. Professional baking workshops are held four times a year. Check out what’s on offer.

Post script:

Just a little update regarding Luna’s thermal performance. Since writing this article, I’ve filled in all the besser bricks with rubble, bits of brick and crusher dust. I’ve also enclosed a sleeve of air surrounding the baking chambers with brick. I’ve bagged the outer shell with mortar, and I’m half way through adding a layer of bottles covered in mortar over the top. Once this is done, I’ll paint the top section in black bituminous paint. At this point, the oven holds an average 100 degrees C some 12 hours after a full bake of about 80 or so loaves. It takes just a bit less than 3 hours to reach baking temperature from cold, though if I really want the oven to be fully ‘soaked’, I’ll pre heat for about 5 hours. I’m yet to gather data on how long the oven takes to heat from 100 degrees, but I think it should re heat in just a couple of hours. All the little bits I’ve done to make it hold heat longer are making a difference; and I can see I’ll be doing more as the need to use the oven more often grows with demand for bread. I’m also noticing that to heat the oven takes less fuel now. This is a bit unscientific, because I’m using different wood from around the farm, but the effect is still noticeable. I still don’t have enough demand to fill 2 days baking, but this will gradually build as I get out and gather more subscribers.

In defence of white squares...

Once upon a time, there was a boy in his back yard, kicking a soccer ball against the side fence. He was still too young for school, but probably too old to be still at home with his Mum. The boy's universe was beginning to stretch beyond the back yard, into the street.

From his vantage point of the front gate, the boy could see the white Holden EH panel van. The driver would park just a couple of houses back from his, open the rear swing up window, and remove a large square wicker basket with a tea towel neatly folded over the handle. He would carefully load the basket up with white squares of bread - these were actually rectangular in shape, but the cross section was totally square. He would cover his load with said tea towel, and would walk from house to house, chatting with any one at home on his way. He dropped off a loaf or two to each residence; he knew where to leave the bread if the owner wasn't home. Money rarely changed hands, except on a Friday, when he would deliver the weekly account, along with the bread.

Eventually, he would get to the boy's house. With a wink, the baker, basket in hand and surprisingly nimble of foot, could lightly direct the boy's soccer ball expertly up the drive, and pass it across to the boy. Without missing a beat, he would hand the boy's mum a loaf, and divide one expertly in half for the boy. The squares had a seam, which tore neatly. This exposed the 'crumb', the absolutely best part of the bread. The boy would sit, soccer ball beside him, and proceed to remove the internals of the crusty, warm 'white square', absorbing the dough with a kind of primal relish.

These memories provided the boy (me) with some indelible lessons; and these lessons are ones which I'd like to share with you in this post.

The first, and most important lesson was generosity. The baker gave me some bread. A simple gesture, but coupled with the baker taking the time to play with me, made it all the more generous. Giving is not something we see as an everyday thing now. It's reserved for occasions - birthday, Christmas etc. And then, it's overdone - we make a theatre of the whole event. Or, we are given something in order to sell us something else - a ‘free gift’. Yet I remember being given not one, but many loaves; it was just something a kid came to appreciate, simply by virtue of being a kid. People looked after you. My world has been forever shaped by this act; my default position has always been one of generosity. My default position is to look after kids. It's in deep.

The next lesson was trust. The boy saw that the baker left everybody their bread each day; there was no question, no payment. The baker knew everybody would look after their bill, and he would never have to think about it. He knew how much bread they needed too - there was no ordering system. It's just the way things were. All our groceries were delivered, because many people didn't have cars (yet - though this would rapidly change). And everyone had a 'bill'. Each week, or whenever it needed to occur, there would be a cup of tea in the kitchen while Mum counted out the exact sum for each person - the grocer, the baker and so on. It was a social thing, more than a financial one. Yes, there were no cards. Cash was currency, and that’s all there was.

Another, more primal lesson, was how good a thing really fresh bread is. I understood it by dipping my hand into it, and tearing out what was inside the crust. The crust was a wrapping for this magical, doughy substance. It wasn't sliced - that was the part you did yourself. We saw it as the ultimate convenience, simply having fresh bread every day - slicing it wasn't even something we thought about - one just sliced ones own bread. I'll hasten to add that this particular bread was tasty. It wasn't overly white - more sort of creamy than white - but it tasted like, well, real bread.

Every meal involved bread. Breakfast was toast and Vegemite. Lunch was a ham sandwich. Dinner was meat, veg and buttered bread on the side. Bread was affordable, staple food. It was a stomach filler. Everyone ate it, and no one complained about their various stomach issues.

Years later, my Dad would take me on his own rounds. He wasn't a baker - he was an accountant. We would jump in our own red and white Holden station wagon (FB, I think; Dad’s pride and joy), with Dad's 'portable' adding machine in the back, along with his 'ledgers' (whatever they were; green hard covered journals in a big box), and head off to the inner west of Sydney.

In those days, the heart of Australia's thriving Italian community began in Croydon, and extended as far as possibly Auburn or Strathfield. Leichhardt was not yet settled - it was more of an industrial outpost back then. It would have been a Sunday mission - Saturdays were usually spent attending soccer games; soccer was considered a 'safe' game, compared to the rugged rugby league. I presume my mother would have been guided in this decision by many Italian mummas.

Dad was a trusted go between; a member of the Anglo world who was also accepted by the Italians. Many of these people had done work for Dad at different times - Dad used to have a grocery store in Croydon, which was in the epicenter of Sydney's first 'little Italy', back in the 1950's. Some of them supplied Dad with vegetables from their market gardens in Auburn; others painted the shop, or did repairs for him. Dad and Mum and I would be invited to Italian weddings, which would last for days at a time.

Dad continued these relationships long after the shop was sold (to one of them - beginning a long tradition of Italian fruit and veg shops in the inner city - but that's another story). Dad had, by this stage, started working a day job, as a company accountant. He still managed to keep all these long time immigrant friends on the right side of the tax man - they didn't understand Australia, or our complex tax system, but Dad did. Again, this was an act of generosity; money was not a primary motivation - at least that’s not how it looked to me, as a kid. Money was only used where other commodities were unsuitable, in the Italian scheme of things. Even then, they would paint your house at the drop of a hat, if they thought it needed doing. Or a mysterious box of vegetables would appear on the front door step, whether you wanted them or not. If all else failed, and there was simply no other way to show the necessary gratitude, a tidy wad of notes would emerge from the back pocket. The commonly accepted technique involved peeling off one note at a time, and gathering each together in an untidy bouquet before handing them over; the standard facial expression offered during this process looked a bit like when removing a thorn from one's foot; unpleasant, but necessary. So very Italian.

These people taught me about respect, about loyalty. This was the underpinning of their world, and it simply would not run without it.

I learned about the 'other' from these people - first hand. Young Italian girls pelted overripe tomatoes at me from a distance, giggling; simultaneously teaching me about survival and lust. And, scraping tomato from my face, I learned about tomatoes. Tomatoes were a very important thing. Dangerous, yet delicious. Ripeness is everything.

Onwards Dad and I would go, until our rounds ended up in Parramatta, at the Fielders Bakery. He would perch me on top of huge hessian bags of grain, and leave me to whoever was working in the bake house at the time to keep an eye on me. Dad would go into the office, and set up his adding machine on the table. For many hours, I would hear the mechanical whirring of the machine as he pulled the handle after each entry. I would pop my head into the office from time to time as Dad worked - and I'd be gone again, into the wilds of the factory with my pump up scooter (something my Dad never forgot to bring when we did our rounds) underneath me.

My memories from this time are a bit muddled - I think the bakery also milled flour, because I distinctly remember these hessian bags full of wheat. I also remember watching the bakers at work, hand turning dough in many large, stone troughs; they would work from one dough to another, using a kind of rotation system. Some of the bakers would squeeze off a little ball of dough between their fingers, and hand it to me. At that age, I had no idea of what was going on in front of me - indeed, it wasn't until many years of running bakeries myself that I was able to piece together these random fragments of memory to make some production sense of them.

These days, the Fielders bakery, which was its name, is long gone - though I think the brand has been absorbed into the conglomerated company that Fielders eventually became. Holden cars are no longer, with the current government ensuring that any automotive industry we may have left is well and truly second or third tier industry, entirely subsumed by the Chinese manufacturing juggernaut.

The Italian community is so well integrated into our own that it is often almost invisible, having newer emigres in ever bigger numbers landing in our old stomping grounds of the inner west of 1960s Sydney.

Change is our only constant, inevitably.

White bread, and in particular the white square, is deeply unfashionable these days - it has become symbolic of all that is wrong with our food system. I hasten to add the white square remains the backbone of the bakery business - it's just that the machines are bigger now; bakers in factories wear white lab coats and monitor systems on a screen. The packers do the dirty work of stacking tins and moving bread crates around. The manufacturing time, per unit of bread, has gone from minutes to seconds.

On the other end of the scale, the franchised retail bakery continues to thrive, while trading on the image of the village baker - which to a certain extent is true, as the bakery is part of the 'shopping village'. The product is uniform, coming from uniform chemistry; the chemistry itself is controlled by the corporation. The franchised baker gets their product range from a series of bags, supplied by the corporation.

These bakeries are little more than a modern form of servitude for all that work in them. Strangely, while many franchisees feel this way, others thrive in a controlled environment. Certainly, these operations are not about skill, or tradition, or quality, and do very little to bond a community - but the illusion is enough, it seems.

I have known many 'died in the wool' bakers who have purchased one of these franchises in the mistaken belief that it would be more profitable than their existing operation. These people will tell you that a profitable franchise is also an illusion; compared to their previous businesses. However, I digress...

It seems to me that the idea of a bakery is powerful in our psyche - but for more reasons than simply to make bread. A bakery is a force for stability, for daily nutrition, for reminding us of our connectedness. It's a place of exchange - ideas, gossip, conversation. For some reason, people feel comfortable around a bakery. They get their daily renewal there. It symbolises constant change, yet also constancy. What is yesterday is gone, like the unsold bread; and today is fresh, and still full of promise. The community square, if you like - though it certainly doesn't have to be white.

Cicadas ate my bellbirds!

It's mid summer here in the Watagans. I can barely hear myself under the din of cicadas. It's so loud that it causes the internal cavities inside my ear to rattle when I go outside.

Right now, there are literally millions of cicadas surrounding my house. I know this, because they are all churping at full throttle as I write. The sound comes in waves, reaching a deafening crescendo before subsiding somewhat, but without end. All day long. Inside the house, it's bearable if I close all the windows, turn on the air conditioning, and do something noisy. Unfortunately, it's really difficult to listen to music, as the pitch of the cicadas removes a certain frequency from one's hearing, like white noise does. Right now it's early morning and not so hot, so I have all the windows open, and fresh air is flooding through the house. Accompanying the din, there is nothing. Most of the birds have vacated - I think that's what the cicadas are doing, by singing at the top of their lungs - they are driving away potential predators while they emerge, mate, lay their eggs and die. Even the dogs have fled to escape the noise. My pack of canine cuties essentially follow me around wherever I am, so if I'm in the house, they are on the verandah. But not today. They are hiding in the cavernous garage with the door half closed to give them a break from the noise. Dogs are such ear driven creatures. It freaks them out when they can't hear properly.

For those of you who have not yet attended a workshop here, the house is surrounded on three sides by dense bush - eucalypt forest, broadly speaking, with quite a steep rise behind us. The rise leads up to an access road, which verges this place. To get up there through the bush almost involves climbing gear, it's so steep. This eucalypt scrub/forest goes on in some directions literally for fifty or more kilometres, as you enter the Watagan mountain wilderness. There aren't too many people up behind us - I would estimate maybe a dozen cars regularly use the access road - and some of them you wouldn't see more than a couple of times a year. It's the first time since I've had the bush bakery here - which is about three and a half years now - that there has been such a cicada onslaught. Pretty sure there have been some cicadas each year, but nothing beyond curiosity was aroused in me. Certainly nothing to remember. I definitely remember the super hot weeks (average 45C for three weeks straight last year), the super wet ones (a couple of years back the rains were so heavy we had to dig trenches around the house so the holding dam wouldn't flood), the super dry and hot ones (last year, again, there were bushfires on the horizon or closer pretty much every day). This place, in a nutshell, seems to attract extremes of climate/environmental conditions. Today, as it has been all summer so far, is no exception.

The bush bakery, of course, is an outdoor affair. It's pretty much a lean-to, pitched on the end of a trailer/bake off unit unit. The bake off unit has a 3 tonne wood fired oven, a tray chiller, a proofer, a make up bench, sinks and dumpout racks. It's open on one side, and has an insulated roof, with your classic corrugated iron deflector above it, installed later to provide a couple of hours' longer protection from the heat when working in 'the box', as I like to call it. It also has a stainless water tank on the roof for its own self contained plumbing system.

I've designed it for a few reasons, which I've discussed in other blog posts (have a look at sourdoughbaker.com.au for the full story about the trailer). Since parking it in its current position, I have made it a more permanent affair, attaching a demountable roof beside it, and a floor built from recycled pallet racking. I've built a very lightweight kitchen around my dough mixer, with shade mesh sides for maximum ventilation. The classroom is beside this, with mesh surrounding a large gazebo. There are blackboards everywhere, and a couple of work benches.

It's been used for baking, consulting and teaching, this space. In the main, it has been an experiment, with an aim of discovering just how little you need to make a few hundred loaves of bread. I think, to that end, it has achieved its purpose. Essentially, you don't need much at all. Indeed, at a future incarnation, I would very much like to strip things down even more. However, there are consequences in choosing to do this. One of them, as has been pointed out at the start of this post, is that for six to eight weeks a year, we are pretty much out of business. It's hard, nigh on impossible, to run a bake in mid summer. The temperatures inside the baking box get up to 50 degrees or more on pretty much every surface - this video is an example of this - and at those temperatures, dough, no matter how cold you keep it - melts. Then, when it rains heavily, you are likely to lose power as the lines gradually become saturated. Over the years I've been able to resolve power issues quite quickly, but when you have over fifty metres to travel to the nearest junction box down the side of a rocky mountain, well, short of investing large amounts of cash, you just constantly try to improve your setup. It's always a work in progress, to put it simply.

So now, in my off season, I get to reassess. It's definitely time to consider this outdoor bakery business. Those of you who have met me at a market or at a workshop know that baking is in my blood. It's very deep in, particularly in recent years when wood fired, third world simple, outdoor sessions were involved. I've been loving it. Right down to my bones.

There's the issue right there. My bones. Over the years, I've managed to stop a couple of cars using mostly my body as the initial deflector. I can tell you, it hurts like hell and I wouldn't advise it. Trouble is, while at the time you don't feel much, the ensuing years and decades make up for it - we are talking, especially, when there has been a considerable amount of time spent on one's feet - as is typical when you embark on baking off a few hundred loaves in a woodfired oven.

The process of pain management these days involves drinking warm water and movement, mainly - but I've used various substances over the years, and somehow one becomes blase about it all. I tend to keep doing the same old thing anyway. I mean, after some of the huge bakes I've done up here at the bush bakery, I'm pretty much incapable of walking more than about ten steps at a time the next day. At times, I've been able to work my way through these periods of extreme pain and stiffness, but as I get older I can see I'll need to really do some proper work on my own body, rather than on my bakery all the time.

So this coming year, I've decided to make some changes. Broadly speaking, I'll be teaching and writing and consulting more, but baking less. I can feel your pain as you discover that there will be less bread around for a while. But hear me out. In the medium term, when I've finished some infrastructural changes (which involve moving the bakery to a more hospitable environment), my aim is to establish a permanent teaching facility which can operate year round. In addition, my new full time school will bake small amounts more regularly, thereby making better use of the resources I have while not destroying my body too much more than necessary.

The idea is to have a bake each week, which students (particularly 300 series students) can run, under supervision at first, until eventually a complete student run bakery emerges. The facility will be used to manufacture a variety of products, with a semi constant production run.

In running the 300 Series workshops, I've become aware of the need for a practical facility where students can hone their skills while they are developing their individual business plan. In many cases, students are at the very beginning phase of their dream bakery, so it is often some years before their own situation evolves sufficiently to be commercially viable for them to fully dive in. The School of Sourdough can provide a venue for their professional development. At the same time, the facility can be a regular bakery, in that a small product range of great breads and cakes can be baked onsite each week for distribution and sale locally.

As far as I am aware, no such facility exists here in Australia. As yet, I have not tied down a suitable venue, though there are a few possibilities which I am chewing over. I want to remain here in the Hunter Valley, as its proximity to Newcastle, the airport, the relative proximity to both the Central Coast and Sydney make the lower Hunter ideal for this purpose. In addition, accommodation here in the Hunter Valley is both plentiful and cheap during the mid week, which is when the production run will take place.

I have already been discussing my vision with a couple of local operators in the accommodation business, but I foresee a need for medium term, budget priced, self contained accommodation for visitors - particularly close by the School, so that students can get around without car hire costs. At this point, I'm focusing on Cessnock and surrounding villages. I feel this town is ripe for something like this, and I'm very open to ideas people might have to make it all happen.

Post Script: It’s a year or so after I wrote this blog post. Since then, I’ve crossed the country and back with my Tour Down South, a traveling sourdough workshop on a specially built, recycled trailer which I tagged The Bush Bakery MkII. I’ve packed up the house/ bakery/ school at Ellalong, and I’ve relocated to a mate’s farm at Wallarobba, about an hour from there. I have begun setting up my school and bakery in a disused dairy shed here. It’s about 3/4 finished as I write this, and in a few weeks I’ll be running my first workshop from this new setup. It’s taken a while to get things done, as we are all just doing the renovations to the dairy in between other jobs. But it will be the School of Sourdough’s permanent home, and I would love to show it off to you! More details about the new bakery in another blog post soon, but if you would like to attend any upcoming workshop, you can follow this link to book.