Direct Woodfired Oven Build (with a difference)

The Back Story

Like a sucker for punishment, I put my hat in the ring. As Paul Kelly said, ‘I’ve done all the dumb things’.

A new client was looking for a wood fired oven and someone to teach her how to make sourdough, and I fitted both requirements. Not that I have ovens on a showroom floor or anything - over the years I’ve designed and commissioned quite a few wood fired ovens around this country, and from time to time these bakeries change hands or close, or grow, and the ovens come onto the market. As I have learned quite a few times now - when you really need a wood fired oven there are none to buy. And when there is one to buy, you don’t need it. So, having already designed what I thought to be a ‘quick to build’ direct fired oven, I volunteered to fill the temporary woodfired oven market void. I confidently informed my client that I could do it in about 6 weeks give or take.

Only a couple of hundred bricks were needed. And some steel I had lying around for just such a project. I’d built a similar oven a few years back so I roughly knew what to do. What could possibly go wrong?

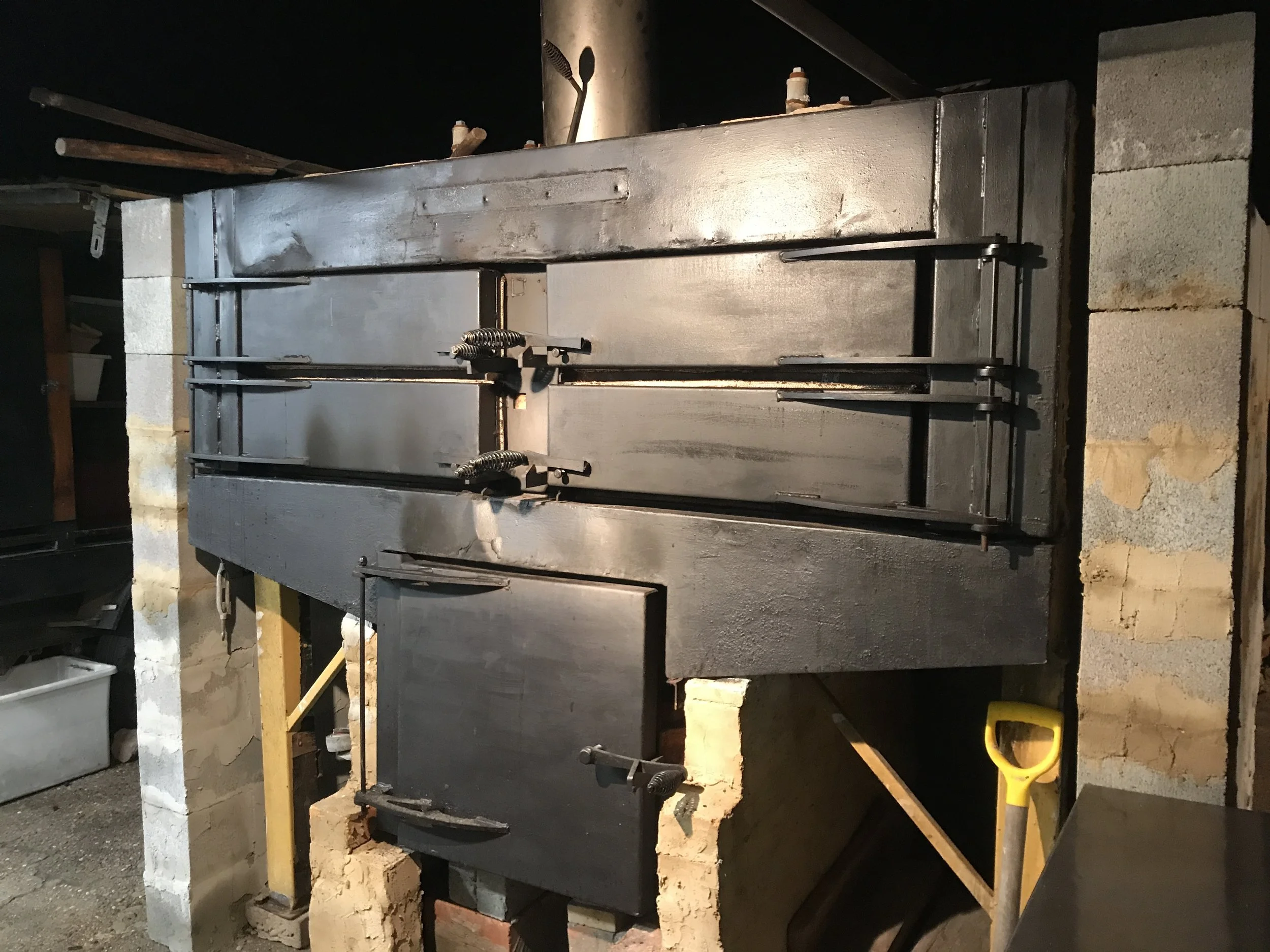

Three and a half months later, it’s finished, and it’s lovely. It turned out quite a bit differently to the original plan in some ways - little refinements which became integral to the design. I’m yet to fire it up (days away), but the design is so simple and robust it will be a good oven to use straight out of the box. It’s made from about 95% repurposed material - just the framework, wheels and mortar are from the hardware store, and the rest has been gathered from wherever I’ve been able to find it.

A ‘Direct’ or ‘Black’ oven

I usually design ‘indirect’ or ‘white’ ovens. These are a type of oven which directs the flue gas around the baking chamber to heat it. They are tricky ovens to get right - the methodology for flueing the gas around the chamber can vary in complexity, but when you get it right (and yes, I have) it creates an even heat in the oven. It also allows you to burn virtually any combustible material as the smoke does not enter the chamber. This new oven design is different - it’s an ‘indirect oven’, or a ‘black’ oven, like a pizza oven, but it has a separate firebox at the bottom, with the flue gases running directly through the baking chamber. Thus, the fuel is limited to wood or charcoal.

Baffle and steam

In order to avoid the issue of too much bottom heat, I’ve developed a combined baffle and steam system which will tame the heat on the bottom deck, and provide large volumes of instant steam, exactly when it’s needed. The baffle system is very important, and over the years it has been the number one wear point in the ovens. I’ve designed this one to be easily removed and replaced. It also has a lot of thermal mass so it creates a steady base heat in the oven.

The oven is a vertical deck style, and the footprint is less than a square metre. It has 5 ergonomically arranged shallow decks made of cast steel BBQ plates. 4 of these plates can be easily slid out and replaced with a rack for smoking or drying. It will hold 20 large free form loaves, or 30 triplet tins. Possibly 80 buns, or 4 large pizzas. It can be used continuously like all my ovens. You don’t have to wait for the fire to become coal, you can use it and fire it at the same time.

The firebox

The firebox design incorporates a gasifier system which shoots hot air into the top of the firebox, causing the oven to burn its own smoke. The degree of gasification can be controlled by the top flue. The oven gets its air from underneath, but during lighting, the firebox is left half open to provide maximum air whilst establishing the fire. Airflow is governed down by closing the base bricks off, forcing the oven to gather air from underneath. This air is pre heated by a layer of stamped brick which warms up as the firebox is used. The oven can be converted to smoking mode by simply shutting down the outlet when hot coals have been established and loading up the firebox with aromatic twigs. The smoke can be made to be hot or cold according to your skill and taste.

The base of the oven is road grate, with heavy duty castors attached. Bricks are laid in channels on the bottom made of steel angle. The steel angle is also attached to the base for vertical framing, and will be tied in above the firebox and then at the top with more angle bolted on. Then I simply lay bricks between the framework. This ultimately makes the oven stronger, as the steel becomes an integral part of the masonry. It also makes the oven transportable.

The firebox itself has two rows of stamped bricks running up either side - these get very hot and provide hot air injection just under the baffle. This is how the oven gasifies. The firebox is lined with firebrick up both sides, which protects the stamped brick from the intense heat the bricks face.

The Baking Chamber

The baking chamber has heavy duty fins built into the brickwork to support the baking shelves or racks. They are positioned 2 brick rows apart, or approximately 160mm height. This is adequate for most sourdough or artisan breads - too much crown height means the base of the breads will cook too quickly - and the steel BBQ plates can be removed for tall baked goods or larger meats. The oven could potentially hold an entire small beast if customised. The BBQ plates could be replaced by racks, if the oven was to be used to create smoked meats or chickens, for example. The oven will also hold about 12 = 14 bread sized cast iron ‘dutch’ ovens as well.

So with that kind of capacity, the oven can cater for big numbers, which is very important from a business perspective. I’ve seen it hundreds of times , the new baker sets up their Rofco and gets a gig baking for their local market only to find they need a second Rofco pretty soon, creating a shackle for their back rather than a profitable business. Every time they grow, they need more equipment. I designed this oven to stretch it’s capacity from very small to quite large, as required.

Hanging The Door

The thing that proved to be the biggest challenge for this build was the door. It is quite large and is effectively a quarter of the wall space of the baking chamber. I had to make it both light and heavy at the same time. It had to be light enough to be hinged from a masonry base but heavy enough to be able to provide some thermal mass. The frame is made from 1 inch steel tube, wrapped in thin galvanised sheet on one side. I had two attempts at getting the insulation right, as weight was a bigger issue than I expected it to be. In the end I used a sandwich construction of cardboard, perlcrete (perlite based concrete - very light), cardboard, cork tiles and finally timber. The framing of the door was made from hardwood fencing, which I had to carve down to reduce weight. Finally I’ve lacquered it with marine lacquer and linseed oil. It’s a sturdy finish, very tough. Inside, the galvanised sheet steel is coated with many coats of high temp paint. Nicely rustic which my client loves. Other finishes and materials can be used as required.

Hanging the door with piano hinge was a two bloke job, but luckily the other bloke was good at doors and came prepared with a door bladder!

It would take up too much space for this article, but the process of building steel plates onto the masonry in order to hang the door took a lot of hours and a lot of errors. I’ll just say that working with steel and masonry is never easy, and total destruction of the brickwork is a possible outcome if you happen to be unlucky. Happily, I was eventually able to get something really solid on, but it actually took two layers of steel and many repetitions of swearwords at great volume to make it work!

Using this multi layered system meant I could get cement nails through the steel and into masonry in parts, while in other places I could use heavy duty bolts. In the end there were about ten anchors in the masonry. The door holds on very well under load. It came in at just under 20 kg when finished.

So now it’s finished!

I hope this oven provides my client with many thousands of profitable and enjoyable hours of use as her business grows and unfolds. It presented me, as the builder, with lots of new challenges. Building this oven took me well out of my comfort zone many times. I’m a baker, not a bricklayer, carpenter, boilermaker or mason. But I had to get a grip on all of these things over three winter months in Gloucester NSW. Nothing is perfect on this oven - it’s flawed in every way - and yet it is quite a lovely thing. You kind of want to hug it.

My aim was to make a baking tool which operates on minimal fuel off grid using repurposed materials. My client asked for a wood fired oven which could bake a variety of loaves and other baked goods in a session. Both objectives should be achieved. The oven is also a smoker, which will, I believe, prove to be very handy.

While I blew my own time budget, I was able to keep the materials budget within 33%. In future commissions, I will have some better strategies thanks to the learning this oven has enabled. And my client now owns a very decent piece of kit which should never need replacing.

So what’s next?

I’ve designed quite a few ovens over the past 15 years, but I’ve only built maybe six or so from start to finish. Almost every build has turned into an epic tale, simply because they are hard on both the body and the brain. Once you get into building them, every bit of the build involves hard physical labour, muscles I didn’t know I still had, and challenges from a practical perspective which involve re doing things many times just to get them right. And lots of research. I never find a whole lot of good info online about what I want to do, EVER. So it’s largely trial and error. It’s for this reason that I’ll declare right now that I won’t be building too many more before I’m done. I’ve decided I’ll make my body and mind available for 6 more ovens, and that’s it. Six. No more, and it’s in writing here so you all know.

In building this oven I’ve also been able to create a matching design for a ‘white’ or ‘Indirect’ version of the same oven. It has a couple of extra layers of brick so it has a slightly larger footprint. It will have a similar if slightly larger capacity, and will have the added advantage of being able to burn waste materials for fuel, rather than only seasoned timber. The ‘white’ version will also have a number of refinements making it more suitable for virtually continuous use. Thus, it will b able to work all day long, every day , as required by shopfront bakeries and cafes.

If you would like to commission me to build one of these ovens, follow the button below. If you would like to discuss more about possibly having one of these built for you, my number is

0409 480 750

Post script Sept 2025:

I find myself the custodian of this amazing oven. I no longer have a venue to house it, so it needs a place to live and work. I need to transport it somewhere soon, and I'm happy to discuss possibilities, which may involve a yearly rental or possibly an exchange for my occasional use. I'm open to hearing your thoughts. Ring me on the number above if you are interested.

Can I leave the grid now please?

This last couple of years has tested a lot of us in small business. Cafes and restaurants have had to pivot into whole new areas as a result of various mandated restrictions imposed from on high. Some have emerged relatively unscathed, while others have had to call it a day. Businesses which rely on the free movement of people also suffered. Tourism and teaching businesses like mine were just two of the casualties.

I was unable to run workshops for the better part of 2 years due to the ongoing threat of lockdowns and various border closures. I know of many local operators who have relied on steady flows of tourists to build their businesses, who have had to either hibernate or move on. Some are emerging from this hibernation now, still viable, but without a whole lot to show for a couple of years of unplanned disruption.

I’m not going to debate whether any of this was necessary, or whether it was an effective approach to dealing with the flu. Economic reality is my focus here. When small business suffers, the long term consequences are felt by everyone, especially in a small community.

And dire economic consequences are the legacy of a couple of years of all this. Now, however, we have a whole new raft of issues to deal with, and these are potentially bigger than the ones we have had throughout this extended flu season.

I’m talking about energy and fuel prices. As of last week, electricity prices for the past quarter from my supplier have gone up by 25%. Fuel prices have increased by between 30 and 50 percent. In other countries, energy price hikes have been even more dramatic, and I’m told that here in Australia we will be facing more price hikes over the coming months. We have already seen massive increases in the price of gas over an extended period, as the previous government thought it would be a great idea to sell off all of our plentiful gas supplies to the highest bidder, and save none for domestic consumption.

If you are a bakery, you might have thought you’d survived the whole pandemic intact, but if your energy and fuel costs have gone through the roof, it’s only a matter of time before the bills start scaring you out of any kind of post pandemic slumber.

Bakeries are without a doubt one of the most energy intensive businesses - the simple fact is that we heat up ovens on a daily basis to bake bread, and this heat is proving to be very expensive to make. We also require energy for refrigeration, and in many cases fuel for transporting our wares. We also are paying extra for flour, as it has to be carried long distances and is affected by these increased fuel costs.

Meanwhile, energy and fuel companies are making record profits. These price increases are not the result of a supply issue, they are to do with our international market systems. A market will very quickly capitalise on disruption, if for no other reason than to preserve or improve the bottom line or market share. We are seeing the very worst of the monopoly focused capital system play out, and many of us will hit the wall as a result - especially those who are ill prepared for these changes.

Early days with Luna

I saw the future many years ago. For my bakery, energy prices jumping suddenly has not been such a dramatic issue. I’ve been heating my oven with waste fuel (timber) for the past 12 years. In my case, my oven can run on sawmill offcut, tree fall or even old pallets. I run my oven a certain amount of the time using biochar, created from waste bread also. This past few years I’ve dived deep into the process of making ovens as well as using them, and so I’ve had the opportunity to experiment with ways of making them run more cleanly, and to get the most out of the wood. The latest prototype from my micro setup has incorporated a naturally aspirated gasification system into the firebox design, which, when running hot, emits virtually no smoke at all. The smoke actually gets burned, creating more and cleaner heat.

On a larger scale, all around the world oven manufacturers are developing cleaner and less expensive ways to heat ovens. In Europe, many old diesel powered ovens have been converted to run on wood pellets, which themselves come from waste material. However, for the average baker in Australia, the capital cost of converting from electric or gas ovens to this biomass technology is beyond their reach.

Old style shopping centre bakeries, operated by a franchisee or family, will need to find ways to pass on these cost increases, and hopefully they can convince their customers that the price of a loaf of bread will have to go up on a fairly regular basis until all this volatility settles down. I’m not sure that all of them will be able to do this, and I anticipate many will go under.

I’ve been helping new bakers to set themselves up as ‘off the grid’ as possible for many years now. All of these bakeries are holding their own at the moment - indeed, many are thriving in their local communities. They all report having to deal with a number of increases to input costs, and yet as a result of using wood fired ovens and the like, these bakeries will whether the energy storm better than most.

But being ‘off the grid’ can be leveraged in other ways, and the definition doesn’t need to be strictly associated with the energy grid. More and more people are seeing the cataclysmic events unfolding in front of us each year as a directive to detach from the system in as many ways as they can. I’m going to call this ‘off the grid thinking’ - in other words, how one can remove oneself from the established system. To do this, it is imperative that we create new systems, which in the end are more directly linked to their customers.

‘Off the grid thinking’ can involve new ways of providing one’s services or products which circumvent or reinvent traditional ways of selling one’s wares. For example, many bakeries once relied on being in a good location to get retail price for their bread. This was once an almost foolproof way to get your bread out there. Now, with main street rents rising every year, the price of retail space is becoming more and more out of reach for the small operator. Only corporate entities with share market support can afford the prime locations. This has led to many bakeries setting up on the edge of small population centers, and they are supplying their bread via subscription systems directly to their customers. Many others are setting up at home, opening up their ‘retail’ from their front porch, and, via the use of social media or email, promote their offerings to fit with their customers weekly routine. Still others focus on a variety of weekend markets to sell their wares. All of these strategies are examples of different ways of doing things, and for many they are proving to be viable and satisfying.

Tiff, from Bread Local in Esperance, has her shop in her front yard every Friday!

There are bakeries who specialise in using their own produce as ingredients in their baked goods too. I know of a farm based bakery who use almost all their eggs and some of their vegetable production in their products. I have a number of clients who mill their own flour to create their bread. I have helped cafe owners to modify their setup in order to bake in house, thereby reducing their input cost. I even have one client who grows their own wheat, mills it and uses the flour in their bread!

To my mind, these are all ‘off the grid’ ways of doing things. These different approaches to the age old craft of baking for one’s community are showing that resilience is the name of the game, and a bit of imagination and some decent research can really make the difference between making it work and giving up because things are out of your control.

I’ve focused on the commercial side of things in this article, as these energy price hikes are effecting us small business operators in very direct ways. However, plenty of home bakers are doing the same thing, and indeed, there is becoming a large overlap between home and professional baker.

I run regular 2, 3 and 4 day intensive workshops for anyone who wants to get serious about their baking business and lifestyle. Don’t hesitate to give me a call or email me on the address at the bottom of this page. Or you can check out just what’s on offer on the link below.

If you’d like to chat about the next step, why not ring me on 0409 480 750? I’ll be able to make some suggestions as to what I think might help you in taking the next step. I’m also very happy to provide mentorship on your individual bakery journey.

Reasons to bake at home (and they are not just economic)

I read an article about the ‘real’ cost of making a loaf of bread at home the other day. The writer seemed to think that labour cost should come into it, and so it was over $30 to make a single loaf. Of course, by the same logic one should make each car separately, and perform every action or task as a stand alone task, and apply a labour cost to it.

So cooking dinner would take forever and cost a small fortune. Your average car would be the same price as a house, and your morning workout would require a bank loan when sustained over a year or so.

Everything in this world comes about as a result of an economy of scale. If you are going to bake a loaf of bread at home, firstly you will most likely make two or more. If you are doing it on a regular basis you will have tooled your kitchen to accommodate the production of bread, so you will have it down pat and very efficient. Your process will integrate into your existing kitchen function, so that you utilise the moment to moment kitchen process efficiently. You will have each bread process down to a matter of minutes.

When I timed my last home bake, it ended up requiring about 15 minutes of actual labour to make two loaves - the rest of the time it was either fermenting in the fridge, or I was shuffling around in the kitchen doing chores and cooking, while my bread was doing whatever it was doing without me.

The idea of applying a labour charge to household chores is problematic. It implies that you should be working constantly; as if to feed yourself, you are taking time out of your working life, so this should be costed.

It’s insane. An unhinged mentality that should be called out at every opportunity. This is why we are in the shit we are in. Too much emphasis on productivity as measured by our labour, as if all we are is a cog in the machine. A value is not attributed to pleasure, to engagement, to the joy of learning and accomplishment. There is no number in the GDP which measures things like life skills and lessons learned. No measurement for how ingenious or resilient a population is. And there’s really not much thought applied to what a healthy mind looks like. It’s considered healthy if it is functioning. If it needs a bottle of wine a day to function, well that’s fine. If it needs a bunch of pills to take the edges off life, that’s okay too. As long as the human cog continues to turn without excessive amounts of grease.

Making stuff, growing stuff, creating stuff - this is the antidote. To create for oneself is indeed a revolutionary act. And if the ‘stuff’ is part of ones own sustenance, even better. Bonus points!

Of course, economics is always lurking around these things. It’s predatory nature is everywhere, especially when the mortgage has just increased and food prices are going through the roof. Here’s how my home baking process stacks up economically, as compared to supermarket sourdough in my country town.

‘Premium’ supermarket sourdough (if you had to put a category on it) is $7.50 per loaf. We have a little bakery now who specialises in sourdough, and they charge $9.50 loaf. So the ballpark ‘average’ retail price is about $8.50.

I can buy reasonably good flour from the supermarket for approximately $2 per kilo. My water is almost free - not even cents per loaf. Salt is perhaps a cent per loaf. Sourdough starter comes from the flour, so the cost is included already. There is also the cost of driving to the supermarket, which I would have to do whether I made bread or not, so I won’t add this.

If I used 500g of flour per loaf, it’s about a dollar. Add in every other ingredient cost and you might come to an extra ten cents, and that’s being generous. So $1.10 total.

When I bake for home, I usually make enough dough for 3 loaves at a time - this is about a week’s worth of bread, or $25.50’s worth of premium sourdough bought from the shops.

Adding up all the time for making it, I would spend no more than 30 minutes. And that’s a generous time estimate too. Most tasks take very few minutes to complete. Cleaning up is included in my time estimate. If I was splitting hairs I would deduct the time I would have spent in the supermarket selecting and paying for my purchases, but I’m not - I just make note of it.

Is this 30 minutes of time that I have had to borrow from elsewhere? Not really. I cook for myself every day. I clean my kitchen every day. I shop for food and supplies most days anyway, so when it all boils down, the extra time to include making bread is negligible.

The other cost to be considered is energy. This can be significant, especially if you are buying yours straight off the grid at retail prices. If this was the case, you might want to add a couple of dollars per bake of 3 loaves. If you have another way - for example a wood fired oven, a solar oven, or have solar panels on your roof to offset this cost, the price will be less, of course. But let’s call it $2 for 3 loaves.

Thus, the actual cost of my 3 home made loaves is $5.30 for the week, vs $25.50 premade. And my bread is better, more satisfying for my soul, and has cost me very little time. I’ve saved at least $20 for my week’s supply of quality sourdough bread.

The numbers stack up, especially over time. A small amount of equipment to improve your process - for example a dutch oven, good kitchen scales, a good quality mixer etc can be another cost, but carefully considered and well used pieces of equipment pay for themselves very quickly.

The investment in learning is important. The cost of my own breaducation was and is expensive, as I have learned almost everything from scratch through trial and error. Luckily, this education has been able to broaden my expertise over the years, to the point where I can show you the results of this experience in a variety of ways.

You can come and be the recipient of my three decades worth for just $300. It will take a weekend of your time, but is there a price applied to having fun?

Gloucester village on the mid north coast of NSW is just a few hours from Sydney, and has numerous accommodation and tourism options. Our weekend workshop intensive is designed to allow you to have plenty of time to take in the town, so get in touch to be connected with what’s available locally.

Phone Warwick 0409 480 750

Keep on keeping on

The end of the School of Sourdough?

The ‘pandemic’ - or how to destroy a small business in just a few easy steps…

Whether it was a global flu, or something more to do with controlling the masses for a couple of years in a very overt manner, lockdowns and travel restrictions meant that for over a year and a half, my primary business, teaching and consulting, had to be paused. I tried to ‘pivot’ things, but in the end the business I created is all about bringing people together to learn and experience something. People were not allowed to travel, so I had no customers.

Towards the eighteen month mark, I began to think it would never recover. Every time some glimmer of hope would be presented, just as quickly, it would be snatched away again. Lockdowns, travel restrictions, changing requirements for businesses all the time - I don’t know how many times people had to cancel attending a workshop at the last minute. I had to cancel workshops many times, as it was just too hard to even attempt to coordinate a bunch of people to come together for a day to learn how to make a loaf of bread.

So my teaching business was on the rocks. Those who follow my story know that I also consult to the trade. Businesses I had been consulting for were put into a kind of intermittent hibernation as well, with many of them unable to open consistently as rules changed every week. Paying me to consult was an expense many of them simply couldn’t carry, so not much work was happening for me to help pay the bills during the extended lockdown period.

And how effective was the lockdown, mask up, coercive vaccination strategy? Here in Australia, we still seem to have high rates of the disease, despite taking all the draconian measures. And pretty soon we will begin to see many issues emerge from shutting down a fair percentage of the workforce for the better part of 2 years. Expect inflation, business closures and higher underemployment to be the result.

Musical Bakeries

While I used the time to build a new oven, the bills could not be paid without work coming in, so I fell behind with the rent. My very patient landlady decided to cut her losses and sell the property I was living and working on (for a tidy profit). When the sale finally went through, I was given a couple of weeks to move everything, and at the time there were no options for relocation of the business. Gloucester, like many rural towns, was filled with people escaping the city, so space was hard to find. So all my gear moved into storage. I lived in the local showground in my caravan for a couple of months.

I had to move twice in a space of 3 months. No teaching was possible, and consultation via zoom was all I could manage to help pay the bills. Needless to say, it has been a struggle to keep on keeping on.

As the lockdowns wore on, my business of some 30 years was reduced to almost nothing. I would be homeless now if it were not for the kindness of some local people and some friends of the business, and for that I will remain grateful. The strength of community is not to be underestimated.

Looking back, how the powers that be thought that locking down an entire nation would solve the flu I will never know, especially as doing this was clearly going to hurt many small businesses like mine. It seemed to me (and others) that the only survivors at the end of it all would be the largest corporations, who had deep enough pockets to carry the can while the rest of us fell over. I suspect ulterior motives. For every newly minted billionaire, there are a million paupers created, and the pandemic has proven this to be true.

Now that some resumption of ‘normal’ life has occurred, we are seeing the price of everything skyrocket. Is this the cost we pay for our ‘safety’? And while we are not actually locked down right now, many people really have to think twice before embarking on a car journey, as fuel prices are going through the roof. The powers that be seem to have created a sort of ‘soft’ lock down now.

The flu is still raging, btw. And a few very big companies seem to have gotten very much bigger. The pandemic has seen the largest transfer of wealth in history.

The baker goes busking

The whole process led me to explore other options, with a complete change of direction for my life and profession being actively explored. For a time, I returned to my musical roots - before I was a baker, I was a musician. So I did a spot of busking and playing at local events. It was great fun, but keeping the wolf from the door proved to be a big ask. Too big for this fella. who has got a lifetime of baking experience, and only a small amount of making a living with strings and voice to fall back on. It kept me sane, singing and playing, but to start again in this configuration proved to be just a bit more than I could manage. Nonetheless, I called my little one man band ‘The Reinvention Engine’. I thought it fitting.

Just when everything seemed lost…

However, some new opportunities for a better site for my school and bakery emerged. With a bit of fancy footwork, I found myself in a new space with cheaper overheads. It’s in an old kitchen factory in the industrial area of Gloucester. I moved in with a bunch of other ‘makers’ back in January.

It’s turning out to be very workable, and I have just finished setting up to resume production and teaching. The return of my equipment from storage has seen me renovate all my baking gear to the best of my ability, and everything looks ship shape again after over a year of inaction. Since moving here I have relocated once again to an outside setup, as the owner didn’t like the so called ‘risk’ of having a wood fired oven near his property. This has shrunk the classroom a bit, but it’s also really great to have things all potentially relocatable and close to home. I’ve really enjoyed the new space and students love it too!

Low tech is beautiful

I’ve used the new barrel oven more than a dozen times now, and while there are some teething issues, it is basically a very good piece of equipment and should serve me well. Once again I have built a decent prototype. It will need more work to make it look pretty, and there are a few little workarounds when in use, but it’s a bloody good unit so far - probably the most promising design I’ve made in the past 15 years or so. But more on that later.

Enrolments for sourdough courses are beginning again, and this last month I’ve been readying the bakery for production once more. There have been some big changes to the way I produce. These have been mulled over for quite some time, and just last week I did a trial bake using the new set up. Having some enforced down time has led me to re imagine my idea of how to go about what I do.

The dough trough

I have incorporated hand dough making into my routine. My trusty mixer was damaged in the fire, and repairs will be done when I can afford them (soon, I hope). In the meantime, I have crafted a large scale dough making trough so I can handle 30kg - 40kg doughs completely by hand.

People say this is crazy. Why would you choose to work hard when you could just fix your mixing machine? When I started out 33 years ago, I made all the dough by hand - and there have been a number of times between now and then when, for various reasons, hand dough making became my normal process. For example, during the Tour Down Under a few years back I was traveling across Australia, teaching my craft, and all the bread I made during the trip came from hand made dough. Before that, our cafe bakery in Hunter street Newcastle was based around a hand made dough system. Going back 33 years, my first commercial bakery had no mixer in it.

More recently, I’ve been using 12kg dough boxes I constructed for the aforementioned Tour Down South. I’d been getting good results, with only some loss of efficiency. I thought that if the capacity of the box was increased, efficiency might also improve. So I designed a big dough trough for making multiple doughs in, like I have seen in overseas bakeries. Now this trough has been finished, I have just begun to use it. I can comfortably manage dough of up to about 30kg at a time, without growing new muscles.

The technique is very gentle and slow - basically it engenders a different way of working. The bread is quite lovely too, being a little moister than before. At the time of writing I am perfecting the technique of mixing large amounts by hand, and I think it will be viable to go this way longer term. I am re thinking my production process, and I like the way this is going.

Once things are generating cashflow again, I’ll fix the mixer - but I want to keep the dough trough as part of the system anyway. It’s a great way to learn about dough development, and is actually reasonably efficient when used to capacity. It is large enough to handle multiple doughs at the same time, and it has surprised me with regard to how easy it is to make dough this way. It’s very a very relaxed way of working, and nothing can break down! Not only that, but cleaning up after making dough is now very easy. Those of us who use spiral mixers will attest to the fact that these machines are a bugger to clean. Not so with a trough!

The Barrel Oven

The new oven will speed up the baking process, as it easily fits 18 or so loaves at a time, and it heats up much faster than any of my previous ovens. I did a trial production run through the oven last week and can confidently report that the oven can easily bake 20 leaves per hour over an extended period. This is almost as fast as my two point five tonne ‘Luna’ oven some years ago, and is only a quarter of the weight.

Overall, the oven has blown my expectations out of the water in a good way! There will be developments on this basic design principle in future ovens. The barrel oven employs some nifty tricks, like a gasification system (no smoke) and a new way of generating large volumes of steam, which has worked better than previous methods.

So my bakery is becoming even lower tech than it was, and I believe it is all the better for it. For years I have been taking my baking ‘off grid’ in a multitude of little ways, and this is another step in this direction.

In these times of skyrocketing energy prices and ongoing uncertainty, being able to control at least a small part of my universe is both satisfying and economical on a number of levels. The bakery now has one less appliance to break down, one less power point required. All that remains now is to work out a way to simply do refrigeration without power. I’m aware of some relatively high tech approaches to this, but I’m keen to play around with the lowest level of tech available. I’m hoping this time I don’t have to have another enforced period of inactivity to think it into existence!

Barrel Oven Build

Early sketch of the Barrel Oven

It’ll only take me a month or so, I said.

Six months later and I’m starting to see the end of the process. As I write this, I’ve done a couple of little fires to cure the masonry, and two trial bakes of 14 loaves each to see how things work. I’ve made some running repairs after each burn, and I’m finally wrapping the whole thing in render. It will be a lovely pink/orange colour when it’s finished.

The Design Brief

Firing it up has surprised me. The oven has definitely achieved part of the design brief - to be able to heat up from cold in 60 minutes. I’ve fired her up four times now, and the last three have made 220C easily. The fourth firing achieved 220C in just 15 minutes! In fact, the fourth burn achieved well over 350C in that time - I didn’t expect this at all.

The second part of the brief was to be able to bake between 12 and 20 loaves per hour. The first trial bake failed at achieving this - the oven achieved 7 loaves per hour at best. At the time I put it down to learning to drive the oven, and having sufficient dry wood on hand to really push it. Ovens, like cars, need to be learned, and they need the right fuel. My previous prototype oven took half a dozen bakes before I was able to drive it along at speed.

The second trial bake was MUCH faster - I only had 14 loaves again, but this time I had the bulk of them baked in under an hour. I will need to do a larger trial bake to get better data on throughput, but I believe the oven would easily be capable of the high end of the original brief - which is around 20 loaves per hour. This is very exciting!

Unfortunately, like half of the country, we are locked down due to Covid restrictions, so I can’t get to the sawmill at the moment, and they don’t deliver. I’ve been buying bags of wood locally, and using whatever else I have to burn from the workshop here. This has meant a mixed result each time, so without a common yardstick (consistent fuel) it’s difficult to get precise data sets, however the fourth burn really showed me just how quick this oven was going to be. I used substantially less fuel than in the previous 3 burns, and yet the chamber was consistently hotter.

This oven has been specifically designed as a small commercial baker’s oven. There are lots of micro bakeries baking once or twice a week, and this oven is intended to be for this type of use. It can heat up quickly, and be capable of baking up to a hundred or so loaves per session without taking an eternity to do so.

My idea is to develop a DIY set of plans for the oven so that people can build their own and get their micro bakery up and running without going into debt. Part of the design brief was to utilise reclaimed and upcycled materials wherever possible. To this end, 95% of the build has satisfied that part of the brief, with only the base, castors and masonry inputs (cement, sand, clay, perlite, lime etc) having to be purchased new. Everything else has been scrounged or purchased second hand.

Finally, I set myself the task of creating a super clean wood fired oven, which would create as little pollutants as possible. Thus, I designed the oven as a ‘gasifier’, that is, to be able to burn its own particulate. To this end, so far I can happily say the gasifier works well. The oven, once heat is in the bricks, expels very little smoke - much less than all my previous ovens by a comfortable margin.

Building a fire in it, as long as one is patient, is also a low smoke process. That’s because the oven has a very direct air supply coming from underneath, with lots of air available to assist with combustion. The fire gets established rapidly, with very basic kindling. I haven’t needed to use super fine dry split timber to get it going. It only takes a few minutes to establish a strong flame in the firebox. At four burns, I can comfortably say this is the most efficient wood fired oven I have ever worked with. It is already the cleanest I’ve designed by a country mile. It seems that my gasifier and high airflow design has been a success.

Progress so far

Here’s a quick summary in words and pictures, now that the oven is nearing completion.

I’ve used various mortars and renders as I’ve gone along, including a special clay render and as well as insulating concrete. Hundreds of hours has gone into researching various combinations of clay, lime, cement, sand, perlite and aggregate. They have been used in different parts of the oven. It has been a process of discovery, and my knowledge of the above materials has expanded exponentially. I’ll also say that once again, the internet isn’t the easiest place to research, with more bad advice than good. But with time, the good stuff begins to shine. It has been a huge lesson in chemistry - which is ironic as I was always the guy who got kicked out of chemistry class at school. Mixing lime or cement with just about anything will yield a chemical reaction!

I’ve used as little steel as possible in this design. There are obvious exceptions - I mean, it IS a barrel oven - though in the end, fortune has allowed me to incorporate steel into places I wasn’t originally planning to use it. For example, it has plate steel decks internally, as I managed to wrangle some great pieces from our local Tip Shop for next to nothing.

Gasification system

To be clear - I have no issues with steel in ovens, it’s just that steel tends to fatigue, so I use it very sparingly - in places which don’t suffer direct flame. Indeed, I designed into this oven a baffle system, which was made of old BBQ plate; the idea being that these would be sacrificial, and would allow the barrel to be spared from direct flame. It turned out that the baffles slowed the oven down, so they have now been removed. I think the distance between the firebox and the barrel being quite large has done the job instead.

Storm water grid on castors!

I’ve built the whole oven on top of a storm water grid with heavy duty castors attached. It can therefore be moved around. The oven has just under 200 bricks, and weighs about three quarters of a tonne, so this is not something you can do with one person - nonetheless it is transportable.

The heavy plate steel decks work extremely well as a setting surface for the dough - better than brick and more consistent. A pleasant surprise, and as they are thinner than firebrick, they have also allowed a bit more crown height in each deck.

In designing the oven, you have to make quite a few guesses. My ‘back of the paper bag’ calculations led me to believe I would be able to load 40 loaves at a time into the oven - but when I actually used it I could see it would be between 24 and 30. Still happy with these numbers - and if you were really pushed you could cram a few more in.

Steam is created by simply pouring water in to the existing spout at the bottom of the barrel lid. This system works as well as any I’ve made in other ovens.

It is actually possible to put too much water in and therefore restrict the temperature reaching the bottom deck, but used correctly this system is as good as a combi steamer! It produces huge VOLUMES of steam.

The firebox has no flue control on the inlet side, just a sliding steel sheet before the chimney, which restricts airflow while also holding in heat. Once the fire is established it’s pretty easy to tune the flame so that the outlet is quite small, while getting maximum draw from the fire. I have found that the oven seems to be very economical with wood so far, and during the tests it held a bakeable heat for over two hours.

I’ve been adding a thick layer of coarse concrete render to the outside this last few days, and I believe this will further assist heat retention. On the second trial bake, I tested the temperatures of the render vs sections without it, and on average there was an improvement of about 5C from the concrete render. I think I will add another layer or two to really maximise the effect.

My original idea was to wrap the whole oven in high temperature insulation blanket, but I decided this would not be necessary. My logic was it takes a good few hours for the heat to penetrate through the brickwork, and mostly the bake will be finished by the time heat begins to escape.

If I was using the oven every day I might consider adding more insulation, but that wasn’t part of the design brief this time around. Adding ceramic blanket would add weight, and draw up heat from the bricks, thereby slowing the oven down.

Insulation actually does have a heat cost. It is best sandwiched between layers of solid material.

From experience, if you want to hold heat in for a long time, it’s best to make the walls more than a foot thick - and in this oven I simply didn’t have enough room for that, as it is built on the storm water grid. This limits how wide the oven becomes.

Issues along the way

There have been some issues with the clay work internally. Some of it has failed, and I was very worried this might occur. As it turned out, I needn’t have worried - the bits that have fallen off can be replaced with firebrick later. It’s a job, of course, but in the short term it won’t affect the oven or the performance.

I have built the oven door with a steel back and hardwood from old fence palings. During high temperature peaks, the timber began to smoulder a little, so I will have to add some more insulation to the door.

Clay work in the firebox

The build has been characterised by lots of stopping and starting. I have been financing the build via a crowd funding campaign, and as such I had to wait until I had enough cash to get each stage of the build done. Then I approached some old friends and was able to get some larger amounts of cash so that I could finance new tools and some of the more expensive bits.

To backtrack a bit by way of explanation - I’ve written about the fire last year in which I lost most of my tools on this blog. Not having things like angle grinders and paint stirrers and so forth made it impossible to do certain jobs. Thankfully, these old friends and accomplices came to the rescue, and enabled me to rebuild my tool kit. I’m eternally grateful!

Another issue has been the weather. Here in Gloucester over the past 6 months or so we have had a number of extended rain periods, which meant that work on the oven, an outdoor process, had to be halted a number of times while the rain did its thing.

There was also the process of experimentation to do - in this build, I embarked on a number of things which I have never done before, and which the internet had very little information I could leverage. For example, the clay mix to coat the hot faces was a real challenge to get right - too much clay meant the mortar simply didn’t dry for weeks on end, and so I had to redo a lot of fiddly stuff a number of times until it was robust enough to be satisfied it would survive heat.

At the time of writing this, I am doing finishing touches - mostly covering the oven with a thick , iron oxide coloured concrete render. It’s very tough stuff, and should protect the brickwork like a skin. It’s a slow process, and will probably require a couple of coats to really get a good surface seal. I plan to let the render cure for a few days, and then fire it up again for another small bake. It’s looking quite similar to the drawing I did when I started planning the oven, which is quite satisfying.

What’s next?

Once I’ve done this next test bake, I’m hoping to get my usual weekly bake going again. It will be nice to have some regular cashflow coming in, and to finally return to the trade I’ve been involved with this past 30 or so years. It HAS been nice not having to bake each week, but I miss the routine, and certainly the regular income the bake provides.

To everyone who has helped me to finance the build, and to those people who helped me do certain jobs which I was unable to do, I say thank you from the bottom of my heart. Not too much longer now, and you will be receiving fresh woodfired sourdough bread once again!

Risks and rewards of baking with a wood fired oven

Years ago I got the wood fired oven bug. Having used them to bake in for nearly fifteen years now, I would say I’m fully infected. Something about them defies reason, I guess - it’s so much easier to turn on a power switch than it is to gather and store wood to fire your oven, especially for a commercial bakery operation. But somehow, for me the hard way wins every time. Someone asked me a few years back if I would ever consider using a ‘regular’ oven again (in my baking practice), and without any hesitation I was able to say ‘no way!’ Baking with a wood fired oven is where the fun is. The whole idea of not having the convenience of flipping a switch to bake is a bit challenging for some people though, so I thought I would weigh up the risks and rewards in this article. So, the good stuff first:

The rewards of wood fired baking

Wood fired baking has a number of rewards attached to the process. The first, and most obvious one, is the quality of bread that you bake. ‘Quality’ is something that is really hard to pin down, and yet it’s also so obvious. The bread from a wood fired oven is just more earthy, more real. These are not exactly scientific terms - and if one did apply science to it, I think it would be difficult to quantitatively measure exactly what it is that’s different. I mean, wood fired bread smells different, especially if it’s baked in an oven where the fire is inside the baking chamber. You get the smell and taste of the fire, and I’m definitely partial to this flavour.

Mostly, though, the ovens I work with do not have the fire inside the baking chamber. I use what is known as ‘indirect’ style ovens, so the fire is a separate thing to the baking chamber. In that way, they bake just like any other oven. The flavour of woodsmoke is not part of it at all. Nonetheless, few who have eaten bread from one of these ovens would argue - they just bake great bread. I put it down to the difference between baking with ‘thermal mass’ versus baking using ‘convection’. The former causes the bread to rise with heat which passes directly into the dough, whereas the latter is heated by the air around the dough. So one type of heat goes directly through the dough, and the other goes around it. It makes a huge difference to the way the bread bakes, and to the way the bread’s ‘mouth feel’ is when you eat it. It also means the bread will keep for longer. In short, sole baked or hearth baked bread in an oven which is heated by thermal mass is more robust. It doesn’t ‘soften’ like ordinary bread - it holds its own.

The second reward of baking using a wood fired oven is the cost of operation. Even when you take into account the time it takes to gather wood - whether it’s felling your own, gathering ‘tree fall’ (sticks and branches), or using sawmill offcuts to power your oven - the cost per bake of an indirect woodfired oven is substantially less than an electric or gas oven. Having said that, if you have to purchase split timber from a vendor, your costs may be similar - but anyone who runs a wood fired oven commercially will work out very quickly that fuel is a direct cost and this has to be minimised. My own practice has involved using sawmill offcut for the past six or more years, as I’ve been living within easy driving distance of a sawmill. I calculate that my cost per bake is less than a quarter that of electricity on average.

Which leads me to the third reward. A wood fired oven makes you think about resource usage. Using an electric oven only causes you to worry about how much resource you use when the bill comes in. It’s an invisible factor most of the time. Your only real awareness of resource use is how much it costs you. On the other hand, when you can see the pile of fuel in front of you getting smaller each time you bake, you become aware of the resource you are using. You also become tuned to the qualities of the wood itself - which types burn hottest, fastest or longest. And when you fell your own timber, you see just how many loaves a single tree can bake. This type of consciousness is something I believe we all could use to our advantage when it comes to lowering our footprint on the earth. I guess the word to describe this reward would be ‘connectedness’. A wood fired oven helps the user to connect to the environment meaningfully.

These three rewards, for me, are enough. There are others, though. A big reward is not having to hook up three phase power or commercial gas supply in the first place. If you are wanting to bake from home, as so many people are now, the cost of this can be crippling, and simply makes the whole enterprise unviable before even leaving the planners desk. A wood fired setup can enable people to run their own show with very little capital, and longer term can also help them to keep their running costs down. A fully off grid setup is also possible, which means the baker isn’t affected by power outages. These can really throw a spanner in things when you are half way through a bake and the power goes down.

And the risks…

Wood fired baking does raise some issues though.

Wood fired ovens create smoke, and this can have an affect on air quality.

Working a wood fired oven involves a bit more labour than using a regular oven too, and this has to be factored in to the cost of operation.

High thermal mass ovens take time to heat up, and this is a resource use issue which needs to be carefully managed.

Wood fired ovens also tend to radiate a lot of heat from opening the firebox, so they need to be carefully planned in to the bakery so as not to create too much heat or smoke.

Using a woodfired oven in a fire prone area could potentially be an environmental risk.

Lets unpack these risk issues one at a time. The first is smoke. An inefficient oven creates smoke, as smoke itself is unburnt particulate. A pollutant to be avoided or at least reduced. There are two parts to this - operation and design. From an operational view, the fire has to be managed at all times. A smouldering, slow burning fire generates smoke, especially when fuel is introduced. However, a fast burning fire creates less smoke. Thus, a fast burning fire is desirable, no matter what type of oven you are using. This can be quite an art to master. In the end, fires are smoky when they are first lit, and then as they establish, the smoke becomes less. Learning the art of running any wood fired oven takes time, and this is something people have to learn how to do properly if they want to keep doing it for a long time.

The second part of smoke management is oven design. There are a number of things which can be helpful if addressed at the design stage. The first is the way the firebox works. In a direct oven, where the fire is inside the baking chamber, the internal shape and proportion of the oven is critically important. These ovens can be shockingly smoky, especially if the fire can’t get the right amount of air to burn efficiently. However, a good design coupled with skilled management will minimise the issue.

Indirect ovens, or ovens which have a separate firebox, have an advantage here, especially if properly designed. These ovens can utilise a smaller, well ventilated firebox, which, when the fire is established, have so much heat stored in them that they burn their own smoke. I have been working on what I term ‘high airflow’ fireboxes for some years now, and all my designs incorporate this principle as the basic starting point. In my latest design, which I’ll be writing about in an upcoming article, I have incorporated ‘gasification’ as a central tenet of the way the firebox works. I have used it before with limited success, but trials of the latest approach have so far shown me that this is the way to go. My barrel oven design has the entire firebox built as a gasifier. Stay tuned for more about this when I have finished building the oven.

Another design initiative to minimise smoke is the way the chimney works. The height of the chimney in any oven is critical. The chimney should be made high enough to lift the smoke away from nearby buildings and into the atmosphere where it can disperse rapidly. Having a tall chimney also allows the fire to draw batter, which in turn leads to less smoke coming out. Often, a smoky oven can be improved by simply extending the chimney. Of course in some cases a chimney being made longer can cause the oven to draw less efficiently - but this is mostly because the firebox cannot establish enough airflow to push the smoke fast enough up the chimney in the first place.

Running a woodfired oven means feeding it with fuel on a regular basis, and this in itself brings us to the next issue: labour. There’s no getting away from this issue, but it can be minimised by thinking through the baking process carefully.

Most bakers will be doing preparation duties while they are warming the oven, utilising their time efficiently while the oven is heating up. They will time the production and baking carefully so that everything works in sync with the oven. The ideal is to run production so that the oven is optimally hot at exactly the right time for loading, and then once the oven is loaded, it is kept full until the bake is finished, with no gaps between loads. There is also some labour involved in preparing and storing wood. Having a wood splitter or using fine offcut can minimise this, but it has to be factored in nonetheless.

The issue of heating large thermal mass can be minimised by the way a bakery is run, as well as in the way the oven is designed and insulated. Bakeries using the oven on multiple concurrent days achieve efficiencies by the effect of heat being held in the thermal mass from the day before. Wrapping the oven in the right amount of insulation to best store heat reduces the inefficiency of having to heat the thermal mass from cold each time.

Another solution to this issue can be to design the oven to heat up quickly from cold. My barrel oven is specifically designed to do this, as the thermal mass is outside the baking chamber, rather than inside it. Thus, heat up time is minimised. This type of oven is best for weekly bakers like me.

Using my travelling oven in Western Australia some years back. The terracotta pots on the top of the oven are ‘heat sinks’ - I heated them up on the top of the oven and then transferred them to the proofer to heat it.

Heat and smoke from the firebox is an issue with all woodfired ovens. Again, it can be minimised by bakery design. I like to put my wood fired ovens outside if possible, where there is separation from the bakery production space, and where there is plenty of natural airflow. I tend to wrap these outside baking areas in shade cloth or similar to minimise the possibility of flies or dust or smoke. If an oven must be placed inside, there should be some thought as to internal ventilation of the space. As anyone who has worked in a bakery will tell you, this is not an issue specifically for wood fired bakeries. Any workspace with a big oven in it is going to get hot, so proper thought around this issue at the planning stage is essential.

Using a wood fired oven in a fire prone area is another real issue, though it is also one which is fairly easy to mitigate. The simplest solution to reduce potential embers escaping from the chimney is to install stainless mesh (there is an Australian Standard mesh available for exactly this reason) on the chimney outlet. The mesh is fine enough to prevent ash passing through, though you need to design the mesh protector in such a way that airflow is maintained. This can be done by fashioning the mesh into a tall cylinder so that air between the holes is maximised.

Some wood fired ovens spew out embers fairly easily, while others don’t. In a well designed wood fired oven, embers are either burnt before exiting the oven, or pass around a number of turns and twists before heading for the flue outlet. Each turn captures particulate.

If your oven is allowing embers to exit in the first place, this shows it isn’t very efficient. This is definitely something to become aware of, and is important in a management sense, whether you are in a fire prone area or not.

Barrel Oven Sketch

In my next article here I’ll be talking about my latest oven build, the Barrel Oven. It’s a small commercial wood fired oven, capable of baking about 30 - 40 loaves at a time. This one has been specially designed for occasional bakers like me, who do not bake on a daily basis. We need an oven to be able to heat up really quickly, and one which will use as little fuel as possible. This design is a refinement of my original barrel oven, which I built about 8 years ago. I’ve incorporated gasification into the design, as well as some new tricks to make living with the oven long term more enjoyable.

At the time of writing this, I have not completed plans for this oven as a DIY project - but I do intend to, once the oven has been commissioned. If you would like to support the build, I have been running some crowd funding campaigns to help with building costs and retooling my bakery. All support is welcome, and once the oven is finished I will match your contribution dollar for dollar with services or bread. At the time of writing, the Barrel Oven is nearing completion, but extra support is still needed, as there is still a bakery to rebuild!

Note: Since beginning the build, I have had lots of support from friends of the bakery directly, as we were beset by a fire late in 2020. This support has been through another channel, which can be linked here. This one shows total contributions towards rebuilding the bakery, including direct contributions and Gofundme ones as well. I’m eternally grateful to everyone who has assisted so far. You will not be forgotten!

My thought funnel

It’s been a long year for everyone, and it’s only halfway through.

Covid 19 seems to have turned most people’s world around - certainly in the cities. We’ve learned that the disease is transmitted by the air - it’s in the wind, so to speak. It’s everywhere around the world, quick as a flash.

While country folk missed out on the brunt of the pandemic, rural Australia has had to deal directly with other issues.

Here in the land down under, Covid come hot on the heels of the worst bushfires we’ve had in many years. These bushfires were the result of the worst drought in living memory. The country around us just turned to dust. It was hard to watch.

Then La Nina kicked in, and the weather did an about face. We have had widespread floods on the eastern side of the country. Where I live in Gloucester NSW, for example, was flooded for the first time in 42 years back in March. As I write this, rural Victoria is in flood. Intense rain has replaced intense heat.

So we have pestilence, fire and flood. Did I mention plague?

Here in NSW, we currently have plague of mice. This is an even bigger issue than Covid for country people, as crops are lost, and years of hard work are destroyed. If the plague isn’t under control soon, we will soon have famine, because the mice are eating all the grain. Grain feeds humans and animals - it’s the basis of modern society, when you think about it.

Anyway, there has been plenty of ‘biblical proportioning’ going on here in the land down under. The cliche of fire, flood, plague and pestilence is without a doubt top of mind for many. And quite obviously there has been pretty much the same level of intensity everywhere else on the planet. No matter how you look at it, people (and some would say the planet itself) are in some way at breaking point.

This bit of the big picture feeds into my small picture, which I will attempt to unfold for you today. Grab yourself a cuppa and I’ll continue along my thought funnel.

Our western society is built upon the idea of endless growth. To this end, we have ignored science, which has been telling us for over fifty years that climate change is accelerating, and that it’s to do with too much carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. They told us that if we continued causing more CO2 to be released into the atmosphere, the planet would heat up and the oceans would rise.

Our response for the past five decades? We just keep pumping more carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. Why have we done this? Because our economic system ignores the lessons of nature by relying on growth as its primary metric. Nature, at its finest, is a balanced system. There is a cycle of growth balanced by a cycle of decay. Decay itself becomes a life force, as it creates food for growth. It’s a process in constant motion.

We have all been waiting for a significant breakthrough which will solve the issue we’ve created. We place hope in this ever advancing technology; that it will, one day, solve every problem. By betting on our technological future, we can go on buying more and more stuff; it’s business as usual. In short, we need not change our consumption addiction because technology will save us. That is the subtext, and it’s kind of paradoxical.

This is really ‘magical thinking’. And it ignores decay as the balancing element. Decay is inherent in every natural system. Are we witnessing, through all this breakdown, actual change?

I’ve always thought that change is in the individual, which then flows into the collective. Change has to happen, no matter what - we must evolve or perish. It seems to me we need to evolve the way we think - everything from capitalism to environmentalism; everything needs to be re imagined, right down to a community level. It boils down to two things - the continued willful ignorance of the dramatic changes in the weather we are all experiencing, and the social changes which have been exacerbated by the ‘pandemic’, but which really have been occurring very slowly for a long time now, as we have all migrated from the physical world to the virtual one. These social changes are significant too. We are now remote global citizens, connected by the internet. For most of us, the computer screen has become the portal to everything else in our lives. Including each other.

Consider this as a ‘big picture’ background to the small picture I want to unfold.

I have been quite fortunate with regard to this worldwide smorgasbord of cataclysms. I live and work in a small rural community. It has been directly affected by the weather, and indirectly by the flow on effects of our responses as a nation to the pandemic. Lockdowns in the cities, border controls and quarantine restrictions have altered things here in some ways. Nonetheless, life goes on for us without huge change. The pandemic has actually boosted tourism in our region. It has also caused the cost of living here to skyrocket, as city dwellers escape to the country, forcing rents and house prices up. So a mixed bag; some good things and some not so good.

I’ve been trying to stay on top of an entirely different set of circumstances. Back in November I had a fire here at my partially completed ‘new’ site in Gloucester. The details of that event are here if you are interested. In that fire, I lost my beloved bakery trailer, the little one I called the Gypsy. That trailer started life as a mobile bakery shop to sell bread at markets. After I stopped doing markets, it was repurposed to become a tiny bakery and mobile classroom on the Tour Down South a few years back. When I returned, it became a part of my Community Supported Bakery, doing the proofing for the bread. Since moving to Gloucester I refitted it to carry the prototype small oven mentioned in the article linked above. That’s when it became part of the fire which engulfed pretty much my whole enterprise. Now it’s a pile of twisted metal, charred wood and ashes.

Growth and (rapid) decay, you might say.

And just to make matters more, well, interesting, I’ve managed to revisit an old ankle injury from my motorcycle riding days. It started as a minor issue, but it grew to the point where I was laid up for months, with twice weekly visits to the local health centre. No commercial baking was possible during this time. Nor any physical work. Not much of anything, really. I had plenty of time to think things though.

Probably too much.

I’m slowly mending now. Still a way from good health, but things are beginning to take shape. My body is healing, and the thoughts in my head are resolving.

I came very close to calling it a day, baking wise. When you add up all the trials and tribulations I’ve had in my long three decades as a professional baker, the case against continuing in this profession is pretty strong.

It’s worth noting that my body has kept me baking for over thirty years, and walking on the planet for sixty or so. Thus, I’ve given just over half of my body’s useful life to the ‘trade’. You only get one body. Baking, like any other physical trade, is tough on the body.

I didn’t start my first bakery to become a baker. I did it to find a substantive use for organic grain. I’ve written about this before, so I won’t cover it here. I made my naturally fermented bread, the bread that made the bakery, to answer a need (no pun intended). This was for decent, nutritious and tasty bread. Bread that made a meal. Bread that satisfied something deeper.

Back when I started out, organic wheat farmers had no manufacturers to help them get their grain into volume production. They could grow it, but they needed volume users like bakeries to justify the expense of going organic.

I decided to create the first (to my knowledge) ‘organic’ bakery, without the faintest idea of how to do it. I just followed my feet. I ended up loving the act of baking, of being a baker.

I believed in what I was doing then, even though I wasn’t actually a baker and had, prior to this, no pressing desire to become one. But that’s what I became anyway, just doing what I thought was needed. Over many years, I baked thousands upon thousands of loaves. Demand always outstripped supply, so I started to pay people to help, and to buy machines to help me make thousands more. I kept growing my bakery, with nothing but belief in what I was doing. There were some good years, and then there were some grindingly bad ones. I made some bad investments, some bad decisions. I lost my way, and then I lost everything else.

I learned the true meaning of capitalism the hard way. It’s a blood sport, and there are winners and losers. I’ve been on both sides.

But still, I found ways to bake. People told me the bread I made was an essential part of their diet, just as it was for me. Other artisan style bakeries sprang up, and they began making more (and better) bread than mine. Other bakeries began using organic grain too; totally organic milling companies sprung up, and established flour mills started to source organic grain as well. Organic flour was on its way. Organic grain was commercially viable and nutritious bread was now available.

Along the way to this successful outcome, I taught many small baking teams, and learned from them as well; bakers and bakeries sprung from my enterprise; many are still baking to this day. If my objective was to get organic grain into production, then my job was well and truly done. But then the life of a sourdough baker began to work its way into me.

It is a different way of baking, making naturally fermented bread, and the skillset required is something that takes many years to really master. You can’t create satisfying sourdough by adding ingredients and out pops a loaf. It’s like a culture, and inoculation begins in many small bakeries, like mine, all around the world. These bakeries have either rejected the chemically enhanced baking practices of the mainstream bakeries, or they just fell into it through the process of discovery. The trade has shifted, with proper artisan bakers being in demand now. They get decent pay and are treated with a degree of respect which didn’t exist when I started out. Bakeries were already mechanised then, and a baker was pretty much a process worker in a large machine.

I had replicated the machine through my own enterprise, and I came to think that I had unwittingly joined the enemy. It took me a while to rethink my position, and even longer to build the kind of bakery I wanted - one where nobody was enslaved. I had been enslaved by the need for capital but I didn’t see it until it destroyed my business.

Fifteen years ago, I started to think about how one could simplify things in the baking business so that ‘capital’ was not part of it at all. This started with the use of wood fired ovens, and then developed into things like community supported bakeries, co ops, social enterprises, and then teaching people about naturally leavened bread.

I figured that If enough people knew how to do this stuff themselves, I wouldn’t be required to do so much baking - it would let me off the hook! I shared my knowledge very freely, until I had to charge for it - another paradox. This past fifteen years or so, on average I have taught about a dozen people a month the basics of sourdough. Very roughly, that’s a couple of thousand peeps directly learning the fundamentals of sourdough and naturally leavened bread making. And through my website SourdoughBaker.com.au, I taught many thousands more.

Sometimes I feel all ‘baked out’, though, and I try to have as little to do with the world of sourdough bread as I can, beyond simply eating it.

Yet I still want to bake! And it seems people still want the bread I bake. Baking offers me connection, a rhythm of life, and cashflow, though if I was hard nosed enough to work out the hourly rate for what I bake, I’m pretty sure I would be looking for alternative ways to earn a living. Nowadays I just bake for subscribers, using the Community Supported Bakery (CSB) principle so that there is no one person carrying all the debt. There is a community of interest sharing in resources for their mutual wellbeing. The baker gets to bake and be loved by his customers, and the customers get the love which the financially unencumbered baker can provide through their bread.

Often people don’t appreciate that those expensive loaves are not actually making the baker rich - they are part of the bakery’s debt structure, because baking equipment is generally pretty expensive. Thus, a Community Supported Bakery spreads the debt among all the customers, and removes the bank from the equation.

So here I am again. My Community Supported Bakery continues to be a work in progress. It’s like the phoenix, rising from the ashes of itself so many times. Now, however, I’m interested in returning what I have learned to the wider community. I want to help bring possibility to fruition. I see a place in the scheme of things for ‘tree change’ bakeries and other food based enterprises to really make a difference in this very confusing world. People who come to the baking business for the right reasons, people who want to have a small footprint but a big legacy, people who want to work with less and who want to minimise waste and create something meaningful for others with their own lives and enterprises- you are my kindred spirits, and I hope I can help you to do the thing you want to do.

So where does this thought funnel lead me now? I want to concentrate on the things which disrupt the corporate mess we have are now mired in. To this end, I would like to do what I can to influence our course of action so that we don’t destroy this beautiful organism we live in. If we can get back to meeting each other, learning about our local communities while attending to their needs; if we can see the process of enterprise not as an exercise of applying capital, but as a creative act, akin to art; if we can reinvent technologies which aspire to self sufficiency and simplicity; if we can consume less; if we can make quality stuff which lasts long after we are gone; if we can learn to waste nothing; these things matter and I want to get behind them in any way I can.

So i’ve decided to carry on for a few more years. I’m going to bake for my people and advance the CSB model locally. I’ll continue to teach people of all levels how to bake, but in a different way. It’s going to be more immersive, and more focused on low tech, hands on baking. I’ve been consulting to the trade for many years already, but now my focus will be on helping what I call ‘tree change’ bakers get themselves up and running without becoming enslaved to the capital cycle. I’ll be showing various ways of running micro bakeries which have the baker themselves at the center, so that families can prosper rather than just businesses.

To this end, I’ve designed two ‘low capital’, wood fired commercial ovens which people can build themselves, with a minimum of capital outlay. These ovens will do an excellent job of baking, while keeping the baker out of debt. The designs are based on my past ovens, but without all the complex fabrication my previous ovens have required. These are truly ‘third world simple’ pieces of kit. I hope to have the process of building them well documented so that anyone can get in touch and be able to get started on their own. I’m offering virtual backup on the build process too, so that each oven built works as it should, for a very long time. Yes, I’ll be charging for the design and support, but it will be a one off fee which won’t have a time limit attached.