Risks and rewards of baking with a wood fired oven

Years ago I got the wood fired oven bug. Having used them to bake in for nearly fifteen years now, I would say I’m fully infected. Something about them defies reason, I guess - it’s so much easier to turn on a power switch than it is to gather and store wood to fire your oven, especially for a commercial bakery operation. But somehow, for me the hard way wins every time. Someone asked me a few years back if I would ever consider using a ‘regular’ oven again (in my baking practice), and without any hesitation I was able to say ‘no way!’ Baking with a wood fired oven is where the fun is. The whole idea of not having the convenience of flipping a switch to bake is a bit challenging for some people though, so I thought I would weigh up the risks and rewards in this article. So, the good stuff first:

The rewards of wood fired baking

Wood fired baking has a number of rewards attached to the process. The first, and most obvious one, is the quality of bread that you bake. ‘Quality’ is something that is really hard to pin down, and yet it’s also so obvious. The bread from a wood fired oven is just more earthy, more real. These are not exactly scientific terms - and if one did apply science to it, I think it would be difficult to quantitatively measure exactly what it is that’s different. I mean, wood fired bread smells different, especially if it’s baked in an oven where the fire is inside the baking chamber. You get the smell and taste of the fire, and I’m definitely partial to this flavour.

Mostly, though, the ovens I work with do not have the fire inside the baking chamber. I use what is known as ‘indirect’ style ovens, so the fire is a separate thing to the baking chamber. In that way, they bake just like any other oven. The flavour of woodsmoke is not part of it at all. Nonetheless, few who have eaten bread from one of these ovens would argue - they just bake great bread. I put it down to the difference between baking with ‘thermal mass’ versus baking using ‘convection’. The former causes the bread to rise with heat which passes directly into the dough, whereas the latter is heated by the air around the dough. So one type of heat goes directly through the dough, and the other goes around it. It makes a huge difference to the way the bread bakes, and to the way the bread’s ‘mouth feel’ is when you eat it. It also means the bread will keep for longer. In short, sole baked or hearth baked bread in an oven which is heated by thermal mass is more robust. It doesn’t ‘soften’ like ordinary bread - it holds its own.

The second reward of baking using a wood fired oven is the cost of operation. Even when you take into account the time it takes to gather wood - whether it’s felling your own, gathering ‘tree fall’ (sticks and branches), or using sawmill offcuts to power your oven - the cost per bake of an indirect woodfired oven is substantially less than an electric or gas oven. Having said that, if you have to purchase split timber from a vendor, your costs may be similar - but anyone who runs a wood fired oven commercially will work out very quickly that fuel is a direct cost and this has to be minimised. My own practice has involved using sawmill offcut for the past six or more years, as I’ve been living within easy driving distance of a sawmill. I calculate that my cost per bake is less than a quarter that of electricity on average.

Which leads me to the third reward. A wood fired oven makes you think about resource usage. Using an electric oven only causes you to worry about how much resource you use when the bill comes in. It’s an invisible factor most of the time. Your only real awareness of resource use is how much it costs you. On the other hand, when you can see the pile of fuel in front of you getting smaller each time you bake, you become aware of the resource you are using. You also become tuned to the qualities of the wood itself - which types burn hottest, fastest or longest. And when you fell your own timber, you see just how many loaves a single tree can bake. This type of consciousness is something I believe we all could use to our advantage when it comes to lowering our footprint on the earth. I guess the word to describe this reward would be ‘connectedness’. A wood fired oven helps the user to connect to the environment meaningfully.

These three rewards, for me, are enough. There are others, though. A big reward is not having to hook up three phase power or commercial gas supply in the first place. If you are wanting to bake from home, as so many people are now, the cost of this can be crippling, and simply makes the whole enterprise unviable before even leaving the planners desk. A wood fired setup can enable people to run their own show with very little capital, and longer term can also help them to keep their running costs down. A fully off grid setup is also possible, which means the baker isn’t affected by power outages. These can really throw a spanner in things when you are half way through a bake and the power goes down.

And the risks…

Wood fired baking does raise some issues though.

Wood fired ovens create smoke, and this can have an affect on air quality.

Working a wood fired oven involves a bit more labour than using a regular oven too, and this has to be factored in to the cost of operation.

High thermal mass ovens take time to heat up, and this is a resource use issue which needs to be carefully managed.

Wood fired ovens also tend to radiate a lot of heat from opening the firebox, so they need to be carefully planned in to the bakery so as not to create too much heat or smoke.

Using a woodfired oven in a fire prone area could potentially be an environmental risk.

Lets unpack these risk issues one at a time. The first is smoke. An inefficient oven creates smoke, as smoke itself is unburnt particulate. A pollutant to be avoided or at least reduced. There are two parts to this - operation and design. From an operational view, the fire has to be managed at all times. A smouldering, slow burning fire generates smoke, especially when fuel is introduced. However, a fast burning fire creates less smoke. Thus, a fast burning fire is desirable, no matter what type of oven you are using. This can be quite an art to master. In the end, fires are smoky when they are first lit, and then as they establish, the smoke becomes less. Learning the art of running any wood fired oven takes time, and this is something people have to learn how to do properly if they want to keep doing it for a long time.

The second part of smoke management is oven design. There are a number of things which can be helpful if addressed at the design stage. The first is the way the firebox works. In a direct oven, where the fire is inside the baking chamber, the internal shape and proportion of the oven is critically important. These ovens can be shockingly smoky, especially if the fire can’t get the right amount of air to burn efficiently. However, a good design coupled with skilled management will minimise the issue.

Indirect ovens, or ovens which have a separate firebox, have an advantage here, especially if properly designed. These ovens can utilise a smaller, well ventilated firebox, which, when the fire is established, have so much heat stored in them that they burn their own smoke. I have been working on what I term ‘high airflow’ fireboxes for some years now, and all my designs incorporate this principle as the basic starting point. In my latest design, which I’ll be writing about in an upcoming article, I have incorporated ‘gasification’ as a central tenet of the way the firebox works. I have used it before with limited success, but trials of the latest approach have so far shown me that this is the way to go. My barrel oven design has the entire firebox built as a gasifier. Stay tuned for more about this when I have finished building the oven.

Another design initiative to minimise smoke is the way the chimney works. The height of the chimney in any oven is critical. The chimney should be made high enough to lift the smoke away from nearby buildings and into the atmosphere where it can disperse rapidly. Having a tall chimney also allows the fire to draw batter, which in turn leads to less smoke coming out. Often, a smoky oven can be improved by simply extending the chimney. Of course in some cases a chimney being made longer can cause the oven to draw less efficiently - but this is mostly because the firebox cannot establish enough airflow to push the smoke fast enough up the chimney in the first place.

Running a woodfired oven means feeding it with fuel on a regular basis, and this in itself brings us to the next issue: labour. There’s no getting away from this issue, but it can be minimised by thinking through the baking process carefully.

Most bakers will be doing preparation duties while they are warming the oven, utilising their time efficiently while the oven is heating up. They will time the production and baking carefully so that everything works in sync with the oven. The ideal is to run production so that the oven is optimally hot at exactly the right time for loading, and then once the oven is loaded, it is kept full until the bake is finished, with no gaps between loads. There is also some labour involved in preparing and storing wood. Having a wood splitter or using fine offcut can minimise this, but it has to be factored in nonetheless.

The issue of heating large thermal mass can be minimised by the way a bakery is run, as well as in the way the oven is designed and insulated. Bakeries using the oven on multiple concurrent days achieve efficiencies by the effect of heat being held in the thermal mass from the day before. Wrapping the oven in the right amount of insulation to best store heat reduces the inefficiency of having to heat the thermal mass from cold each time.

Another solution to this issue can be to design the oven to heat up quickly from cold. My barrel oven is specifically designed to do this, as the thermal mass is outside the baking chamber, rather than inside it. Thus, heat up time is minimised. This type of oven is best for weekly bakers like me.

Using my travelling oven in Western Australia some years back. The terracotta pots on the top of the oven are ‘heat sinks’ - I heated them up on the top of the oven and then transferred them to the proofer to heat it.

Heat and smoke from the firebox is an issue with all woodfired ovens. Again, it can be minimised by bakery design. I like to put my wood fired ovens outside if possible, where there is separation from the bakery production space, and where there is plenty of natural airflow. I tend to wrap these outside baking areas in shade cloth or similar to minimise the possibility of flies or dust or smoke. If an oven must be placed inside, there should be some thought as to internal ventilation of the space. As anyone who has worked in a bakery will tell you, this is not an issue specifically for wood fired bakeries. Any workspace with a big oven in it is going to get hot, so proper thought around this issue at the planning stage is essential.

Using a wood fired oven in a fire prone area is another real issue, though it is also one which is fairly easy to mitigate. The simplest solution to reduce potential embers escaping from the chimney is to install stainless mesh (there is an Australian Standard mesh available for exactly this reason) on the chimney outlet. The mesh is fine enough to prevent ash passing through, though you need to design the mesh protector in such a way that airflow is maintained. This can be done by fashioning the mesh into a tall cylinder so that air between the holes is maximised.

Some wood fired ovens spew out embers fairly easily, while others don’t. In a well designed wood fired oven, embers are either burnt before exiting the oven, or pass around a number of turns and twists before heading for the flue outlet. Each turn captures particulate.

If your oven is allowing embers to exit in the first place, this shows it isn’t very efficient. This is definitely something to become aware of, and is important in a management sense, whether you are in a fire prone area or not.

Barrel Oven Sketch

In my next article here I’ll be talking about my latest oven build, the Barrel Oven. It’s a small commercial wood fired oven, capable of baking about 30 - 40 loaves at a time. This one has been specially designed for occasional bakers like me, who do not bake on a daily basis. We need an oven to be able to heat up really quickly, and one which will use as little fuel as possible. This design is a refinement of my original barrel oven, which I built about 8 years ago. I’ve incorporated gasification into the design, as well as some new tricks to make living with the oven long term more enjoyable.

At the time of writing this, I have not completed plans for this oven as a DIY project - but I do intend to, once the oven has been commissioned. If you would like to support the build, I have been running some crowd funding campaigns to help with building costs and retooling my bakery. All support is welcome, and once the oven is finished I will match your contribution dollar for dollar with services or bread. At the time of writing, the Barrel Oven is nearing completion, but extra support is still needed, as there is still a bakery to rebuild!

Note: Since beginning the build, I have had lots of support from friends of the bakery directly, as we were beset by a fire late in 2020. This support has been through another channel, which can be linked here. This one shows total contributions towards rebuilding the bakery, including direct contributions and Gofundme ones as well. I’m eternally grateful to everyone who has assisted so far. You will not be forgotten!

The saga of my new wood fired oven

Shock Horror! Luna the wood fired oven has been decommissioned!

A closeup of Luna’s firebox recently after having the new V baffle fitted.

After over 7 years of use, Luna was facing yet another bout of major surgery. While this could be considered fairly routine for a well used oven, those who follow this blog will know just how much work I have put in to keeping Luna functioning.

After only a year of use since refitting her with a new steel baffle, the same baffle was completely destroyed by heat. This was a 10 mm thick piece of steel which my boilermaker advisor and collaborator assured me would do the job (at least for a few years) instead of going the whole hog and putting in stainless . Cost is always a factor in these decisions, and our judgement call wasn’t the right one. I expected it to last for at least a few years, as I was only using the oven for a day or two each week. But I watched that baffle gradually burn out over the past couple of months, working around it as best as I could for that time, and found myself thinking deeply about my history with every oven me and the boilermaker have ever created this last 12 years or so.

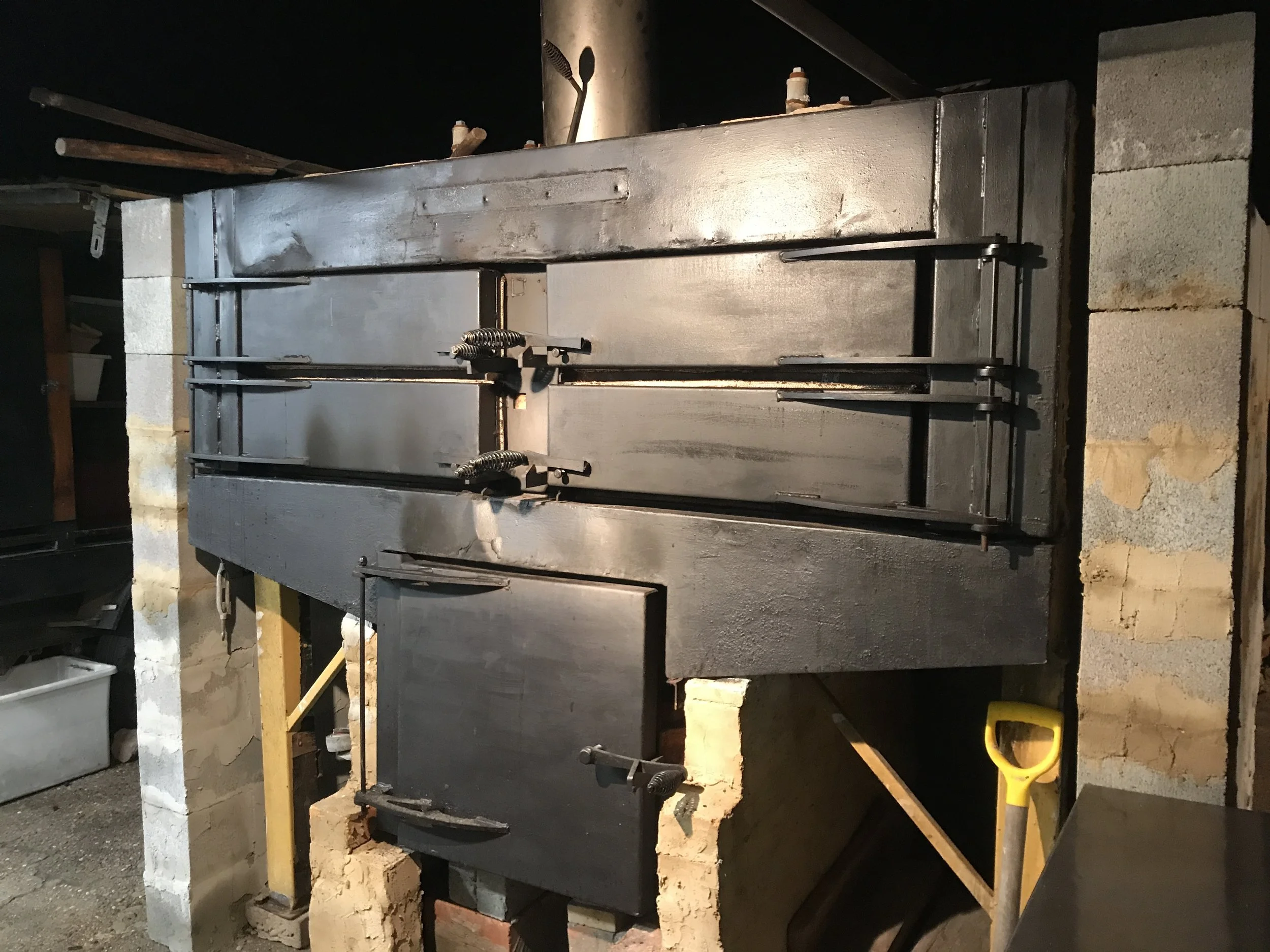

Bertha II and her firebox repairs. Big firebox, and a bugger of a job!

Berth 1, Bertha 2, and Luna, being the names I’ve given to three woodfired ovens I have had a direct and long term association with, have all caused me lots of physical and financial pain. I have crawled inside each of them, as well as other ovens made with our template - in a couple of cases while they were fully hot - and it’s never a pleasant (or healthy) experience. While all of them, after much post production work, have functioned well in the end, they each have had massive problems. These problems usually stemmed from the fact that metal degrades and warps over time, or is simply a very unforgiving material to work with.

Thus, I decided to avoid the material as much as possible in all my future ovens. I’m totally done with the complexity and cost associated with ovens which are essentially using lots of metal to hold masonry in place. Woodfired ovens have been made for centuries successfully with just brick and mortar. Why reinvent the wheel?

I’ve been working on a full masonry design for the past 12 months, and have finally built a small prototype to see how the masonry version of a ‘white oven’ will work. The design has morphed into something quite different over that time; when I look at what I’ve created I can see the original concept, but that’s about it. The way I got to the concept twisted and turned quite a bit.

The new prototype at the firebox stage.

The materials to make the oven evolved - I started with the idea of using common bricks with oven bricks used in various strategic places, which had merit; cheaply sourced common bricks can do the job, especially if you also use high temperature bricks on the parts of the oven where there is a lot of heat. But this prototype was to be built on my trailer, and I was worried they would require a lot of bracing to hold them together. Trailers bump around a lot on the road. Also, weight (at that time) was an issue, and I wasn’t sure brick was light enough.

Then I considered cast cement and AAC (Autoclaved Aerated Concrete), both of which I could cast myself. This attracted me as I could cast exactly to size; if I could cast fairly thin sheets I could save weight. I designed some molds which enabled each piece to lock into each other. The further I went down the casting rabbit hole, though, the more complex things became. The casting process seemed like a lot of fiddling, and was fraught with traps for newbies like me, so this idea morphed into using pre cast cinder blocks and manufactured AAC (Besser bricks and Hebel, being two brands commonly available locally). Off the shelf, at least in theory, it was possible to get pretty close to the correct size for the project. I tweaked the original design a little to accommodate them - then came to a road block - my design worked on an uncommon size of besser brick, being thinner than the usual construction kind. I only needed about six of them, but they were critical to the flue design in the oven. Do you think I could find anyone who would stock or sell me 6? The smallest amount I could order was a full pallet. So I went off looking for other ways to skin this cat.

I’m wandering around various landscaping and building suppliers in my new home town of Gloucester, looking for stuff to build my oven with, when I notice an unusual brick with three large holes. Immediately I see how it could work in my oven. While I wasn’t able to buy it, the retailer put me in touch with their maker - Lincoln Brickworks, just down the road at Wingham.

A quick drive and I’m chatting to the brickmaker himself. Before long he’s showing me their kilns - which coincidentally are wood fired till they get to 700C, then oil fired to take them up to 1300C. Lincoln bricks are one of the last independent brickmakers on the eastern side of the country - and they make their bricks in small batches, catering to the niche of the trade interested in truly bespoke, rustic materials, and craftsman techniques from the past. I’m sold, and the brick maker helps me load up 40 of them to try for my ovens. When I go to pay, they wave me through, saying ‘you’ll be back - we’ll sort it out then!’

Brick sides are on and rendered.

The bricks were used in the final prototype, and they worked as intended. They are stacked directly on top of each other in the side walls of the oven, creating flue pipes for the flue gases to travel along. The flue pipes lead around the oven, transmitting heat from the flue gas directly to the baking chambers. This meant that the baking chambers would heat up quickly, and that I would be reducing a whole layer of brick from my design, making it lighter.

I also built the firebox out of common brick, and lined the insides with firebrick. For a baffle above the firebox, I did some research into concrete, as my local hardware store sold 600 x 600 (2 foot x 2foot) slabs which were about 100mm thick. This was about the right size for the base of the baking chamber, and would save me a whole lot of time and expense with fabricating some sort of lintel to support a brick baffle. This was my first major error.

Then, bang! The concrete baffle exploded!

According to everything I read, concrete could withstand 600C heat. From experience, the internal temps in all my previous fireboxes reached 500C, so I figured I had a bit of wriggle room. I was very wrong. On the first trial firing, maybe half an hour in, I heard a large deep ‘boom’. I checked the baking chamber, and a hole had blown right through the concrete! So much for 600 C! It’s possible the slab I had purchased was not adequately cured - because I had taken temperatures inside the firebox some 5 minutes earlier and it had barely reached 200C at that stage. Far too low, I would have thought, to cause the concrete to react with the heat. Despite this fairly intense reaction, the oven held together.

I visited our local ‘Tip Shop’ (a most wonderful community resource where waste is sorted, displayed and sold for super cheap) and found some really heavy duty BBQ plate steel. I was able to support this underneath the slab, and thereby create a secondary level of baffle. I then used a high temp mortar mix to fill the hole in the slab, and put 30mm oven bricks on the top.

Shelves are added and bricks used in place of a firebox door.

Thankfully, this very quick and cheap repair meant that I could use the oven. I had quite a few subscribers to my bread delivery service (see previous post on my CSB) who, having not received bread during the entire period of relocation and oven building, were starting to lose their minds. I didn’t want to lose them as customers, or to have them lose their minds due to bread starvation, so I was in a hurry to get the prototype fired up and baking.

Over the next 6 bakes or so, I grew quite fond of my prototype tiny oven. It was relatively quick - 15 loaves an hour vs 20 per hour in Luna, which was 4 times the size. It was fast to heat up too - from cold to bake temperature in 2 to 3 hours. It also gave a wonderful kick to the loaves - my original spacing between the shelves was now too small, as the loaves were bigger than they were before by approx an inch! The prototype worked better than I thought it would, and really didn’t require a whole lot of modification, beyond repairing dodgy little bits of my super low budget repurposed construction materials.

But there were some problems. The primary issues were:

A baking chamber door is attached. It opens to a flat 90 degree platform.

getting the door to seal correctly. Smoke from the firebox would creep in under the baking chamber door and taint the bread. The door was a piece of fairly thin steel from a previous oven which had been used as a shelf. The seal between it and the masonry was less than perfect, so I used some ceramic rope and high temperature tape to bog up the gap. It worked, after a couple of less than satisfactory attempts.

creating steam in the baking chambers. Due to my lack of welding equipment (and the lack of welding knowledge) I struggled to fabricate a way of holding water in a piece of pipe. The pipe system has been used successfully in all my previous ovens, but they required a welder to make them. This time I was in a new town and I didn’t know anyone here. Eventually I purchased some rectangular hollow galvanized bar and filled the ends with cement to block them off. Then I cut some grooves along their length with an angle grinder, which allowed steam to escape. They worked extremely well. They held close to a litre of water, which provided enough live, gentle steam to the baking chambers for some 15 minutes at a time.

properly insulating the surrounds of the oven. I built the oven to fit into the existing space on my trailer. There had been a small oven there previously which I used for demonstration bakes and workshops. To save time, I simply beefed up the existing insulation around the wall area and re-did the roof insulation. The floor had a layer of insulation too, as well as a sheet of rubber to isolate vibration from the oven. The oven base was 100 mm hebel, which is, in itself, insulation. The outer shell was made of this also. I figured I had it all covered.

I did not. After the first couple of production bakes, I observed smoke around the top of the oven. This worried me, so I removed the entire roof and replaced it with brick and corrugated iron. So much for weight! I could no longer tow the oven, but at this point I was quite happy for the oven to be semi permanently set up at my new home base in Gloucester.

Fired up for the first time!

After another couple of bakes, I noticed smoke coming out from UNDER the oven. While the top was now fine, smoke coming from under the oven really confused me. There was so much insulation and brickwork around the firebox, it just didn’t make sense. I added another layer of brick to the base of the firebox and the problem seemed to go away. Or it became less obvious, as I now know!

Needless to say, I was inspired by my little protoype. However, I could see that my construction techniques were not up for the long haul, and that I would need to be doing a lot of spot repairs to keep the little oven alive until I could make a bigger, more robust one.

Last week, after finishing the bake in record time, I felt I had mastered the oven, and made all the necessary tweaks for performance I would need to do for a while. I went to bed early and was keen to get the bread delivered the following day. A good bake is a wonderful thing for the psyche.

An early test run alerted me to the need to rebuild the chimney!

I woke to a loud ‘boom’ at about 2.30 am. I could see flickering light through the curtains, and stepped out to find the trailer and a couch in the undercover garden area fully blazing. As I ran to grab the hose, a second couch exploded into flame - I had put them perhaps 8 feet away from the other side of the trailer just two days earlier.

The fire from the trailer had engulfed them and caused the explosions. Luckily the local fire brigade came in 20 minutes or so, but those 20 minutes were I think the longest in my life, as I pointed an ineffectual hose in the general direction of the blaze. The fireys brought it under control in about half an hour. I wandered around on the footpath outside with loaves of freshly baked bread at 3 am for them as some form of thanks.

First bake!

(photo, on B+W film, courtesy of Maira Wilkie)

I lost the trailer, as well as a fair proportion of my power tools. I also lost some printing equipment, and a good deal of pride. I thought I had insulated the section around the oven well, and indeed I did. The problem was under it. I built the oven on AAC (hebel), with fire bricks on top. There was a layer of wool insulation batt under the oven, with a thick rubber matt under that, and foam under that, and finally the timber frame built on the trailer years earlier. The weight of the oven had slowly flattened the insulation, making it less effective. The heat from the firebox had found its way through all the insulation, and had created a smouldering heat issue which had slowly, over quite a few weeks, degraded the timber framework underneath. This simply gave way, the oven tilted backwards, and hot coal spilt out of the firebox, setting the whole trailer alight.

Disaster! Half a dozen bakes later, the fireproofing under the oven fails, and the oven tips over, catching the trailer on fire and destroying it completely.

Apart from feeling stupid at my errors of construction, I felt defeated. It’s taken me 30 years to be at a comfortable place with my craft. I get to bake commercially just once a week, with civilised hours. I have many happy subscribers to my bread delivery service, which has continued each week now for two years or so. I try to impart good info to anyone who wants to know. I’m deeply immersed in my craft, as anyone who has spoken to me will be quick to agree. Many 300 series students have gone on to start their own successful micro bakeries, as a result of my inspiration and guidance.

Over the years, thousands of home bakers have come to learn at my 101 workshops held each month, and many stay in touch, attending numerous workshops to keep their bread making processes improving and growing . I’m deeply happy to be part of the bread making renaissance in Australia. When I began, bakeries were heading away from natural bread; there was not an interest in using organically grown grain or in artisan milling or fermented bread at all. Now there are hundreds of successful bakeries turning out great bread all around Australia, and when I speak to them they are rightfully proud of their product. There are a number of mills creating superb, sustainably grown flour from quality grain. Of all this, I can say I was one of many who worked to make it happen.

The bakery business has been tough on me, and my body. I’ve earned a living though, and I’ve largely been my own boss for a long, long time. I’m rich in what I know, and I’ve been further enriched by the responses people have to my bread, my teaching and my professional guidance over many years. I’m not materially rich, though - I discovered some time ago that I have little interest in material gain beyond what I need to keep going. This I know is both a problem, and a solution to bigger problems.

Thus I find myself questioning whether I should go on; to rebuild, or to find another way of earning a living. I feel like I have been a professional crash test dummy for too long. It’s my own doing, I know. And I do question my sanity from time to time.

In Western Australia teaching Bush Baking a couple of years back, with the trailer on its second incarnation.

So I’m asking you, dear reader, to really help. I have decided to seek contributions to a crowd funding initiative, to help me build a new oven and to rebuild the site, so that I can get the School of Sourdough properly established here in Gloucester. I need to buy materials to build the oven, as well as some new tools and some professional assistance so that the new setup won’t have any issues down the track. If you think I should continue doing what I do, then follow the link below and make a contribution. If I can raise $20K I’ll be over the moon. If I can raise half that, I will still be able to get things up and running again. Any amount will encourage me to continue. Even nice words and a bit of virality by sharing this post will go a long way.

People who can contribute will be rewarded in any way I can - small contributions will get free bread to equal value when the oven is finished - provided you are somewhere in the Hunter Valley region. Bigger ones can receive one on one tuition/consultation to the value of their contribution down the track, here at the bakery or over the phone, if necessary. Really big ones will receive eternal gratitude and whatever else I can give to say thank you. And everyone will be supporting a community enterprise as well as a journeyman baker who needs to know if he’s mad or not. Please chip in and help me get this project finished!

The Rebirth of Luna

Luna’s been rebirthing. You’d think she would have learned!

Luna’s about 7 years old. For an oven built as a prototype, that’s getting on. She’s had a robust, quite eventful life so far. She’s lived in four locations, as well as a short stint living ‘on the road’, as the centrepiece to my first travelling bakery and classroom. She was designed to be a mobile, high volume wood fired oven. She was meant to be light, heat up quickly, and be able to bake 300 or more perfect loaves of bread in the space of a market - which would be around eight hours.

For this task, she was a complete failure. The entire mobile bakery enterprise had a number of flaws, as it turned out. I may well have covered these, and the mobile bakery, in a previous blog post; I can’t remember. Anyway, that’s not what this post is about.

That’s Luna’s bush hideaway. She’s in the box…

Luna found her place as a stationary oven. She lived on a fixed site, still on the mobile bakery trailer, at a bush hideaway in Ellalong, where she performed the weekly baking duties for local Saturday markets with incredible finesse. I knew the difference Luna made - a kind of crust that only a brick oven can give you.

She was always a bit tricky to work with - she liked to be pre heated for a good 5 hours before she would really begin to sing, for example. She had some hot spots (which became completely ‘worked around’, as one does with any old bakery oven), and she needed a major clean out and overhaul every year, or she would block up (and actually melt) in parts. I had to rebuild the firebox a couple of times, and used a crowbar to open up a pathway for flue gases when it fatigued after about 5 years use.

I learned the hard way with Luna, every time, but after each rebuild she returned to work, better than ever. She was, for many years, a ‘work in progress’. She eventually became an excellent oven, capable of baking an average of 30 average sized full sourdogh loaves an hour - provided I was on my game - and more if someone was helping me. She did her job as a test bed and we improved our Aromatic Embers ovens as a result.

When the first Bush Bakery at Ellalong came to an end, I packed Luna up in the trailer, took out her bricks, and parked her in a nearby paddock, where she lived for a few months. I towed her here to the farm, and she was parked again for a few more months. We removed her from the trailer after the Tour Down South, and a boilermaker began the task of refurbishing her, with design modifications we had now applied to some of our other ovens.

Luna was my third prototype. I was the test pilot and outside design consultant. Actually, I became the crash test dummy more often than not. The first two prototypes, both named Bertha, turned out to be absolute pigs of ovens, but pigs which were made to sing for their supper nonetheless, thanks to my need to bake decent bread.

Bertha 1 in Cafe mode. Note bricked plate warmer on top!

Luna was different. We really thought about Luna - all our mistakes taught us what NOT to do. So Luna was a decent oven from the getgo - but she developed some long term issues. That’s why I was always working on her - she took a fair bit of tweaking to make her really sing, I can tell you! So when I left her in the boilermaker’s capable hands, I gave him my wish list - or at least half of it. I knew I’d be doing the other half myself.

This time I wanted to make the flame generated from the fire really stretch, so that it could do the job of heating more cleanly, quickly and efficiently. We needed to get the bottom decks more even too. Back in the day, the area above the firebox was always the hottest part of the deck. It was so hot that I had to set loaves to one side so they didn’t burn.

The boilermaker takes Luna apart with the tynes of a tractor.

Stretching the flame in Luna’s firebox.

The top decks have always relatively slow, so we set out to improve the heat here at same time.

The boilermaker built a more sophisticated and heavy duty baffle system, based on my ideas. He made the baffle itself more angled so that flame was siphoned off better when it runs against it from the firebox. I later bricked the inside of the firebox to further enhance the ‘flamethrower effect’. He rebuilt the firebox to include more brick than before. He also incorporated a whole series of cleaning access tubes to the roof of the oven, so that the area nearest the flue could be cleaned - an issue which had reared its ugly head a couple of times in Luna’s life already.

I’m hoping the changes to the flue system will eliminate the problem of soot build up altogether. I’m fully aware that I may simply be experiencing a case of wishful thinking here. Every designer wants their latest and greatest innovation to work - we always wear rose coloured glasses, to a certain extent. Sometimes, though, it pays to take out insurance. If there was still a build up of soot, despite our new modifications, at least I can now clean it out more easily than in the past.

Luna’s cleaning tubes before they get bricked and mortared.

All this work took many months. Luna was positioned in the middle of a paddock full of farm equipment. When the boilermaker was on the farm, he’d carry Luna’s bits over to the shed on the tines of the old tractor. He’d weld and angle grind and rivet for hours on end. From time to time I’d ‘lackey’ for him - just as I did when Luna was fabricated here on the farm years ago. Only then, as I remember it, I was on crutches. That’s a whole other story. Not this time - I walk pretty well these days.

More heavy duty thermal mass is added before putting Luna back together.

As the work on Luna slowly got done, a bit here and a bit there, the dairy shed also got finished - in much the same manner. A few weeks ago we carried Luna’s 2 finished pieces over to the dairy shed on the tractor, and we put her back together for the first time in a year. Then we positioned her outside the new school classroom and bakery, where she will live for quite a while, I hope.

Luna 2 showing inner layer of brickwork. This will be wrapped with besser brick.

I’ve been bricking her up, inside and out, for the past two weeks or so. It’s slow, heavy work, as a great deal of the brick is in really hard to get at places - inside baking chambers, for example. These baking chambers are only 16 cm high and a metre deep. One slides the bricks in on the end of a metal peel, and manipulates them as best as one can from a metre away. Around the baking chambers there are two layers of brick, and another layer on the top of them. Getting the bricks in place involves climbing up a ladder with brick or bricks in hand, keeping a fresh mortar on the go all the while, for maybe a couple of hundred climbs. Each brick weighs between 2 and 5 kg, and so far I’ve put roughly 500 bricks in and through and around the oven, as well as another couple of hundred inside the baffles, which we did before she was put back together. I’ve only done enough, at the time of writing this, to fire the oven up and make it work.

First layer of brickwork done. The oven is functional here, though nowhere near thermally efficient.

All this extra thermal mass and insulation will become necessary when Luna goes into production mode for the ‘Steady State Bakery’. It will operate as a heat sink, as well as a kind of heat mirror; the thick walls of brick should hold heat for days. Luna will become a super efficient oven.

i was inspired in my design for Luna by spending time at Harcourt Historic Bakery with Jodi and Dave when I did the Tour Down South last year. Their oven is capable of holding high temperatures for days after firing, as it has some 72 tonnes of brick around it. It’s an incredible piece of kit for a 100 year old oven. Dave manages to keep it hot with very little timber each day.

My version only will have maybe four or five tonnes of brick when it’s finished. The principle is similar to the oven in Harcourt though - get the brick hot, and then once it’s hot, keep it there for as long as possible. I’ll be looking for new bakery customers very soon, that’s for sure!

Next layer done. Still have to complete the outer wrapping, add more mass to the roof, and fill the besser bricks with rubble and sand.

Upon firing her up after putting her in place here, I saw that Luna was really a serious piece of flame art now. The firebox works a treat, blasting flame a good few feet each side, in sheets, spread out right under the two baking decks. It takes the oven from cold to baking temperature in just 3 hours, but will do it substantially quicker when it is fired each day or two, as it will retain a lot of heat.

Just a teensie fire here. When I fully blaze the fire, it’s too hot for my camera!

At the time of writing I’m about two thirds of the way through the brickwork. There is an ‘inner outer’ layer of brick around the baking chamber, and another around the firebox. There are two layers on top, with two more layers of grog based on mortar and recycled crushed concrete. There will be another layer of brick and mortar on top as well. There is a layer of besser brick surrounding the three sides, and I’m currently filling these with rubble, glass and sand to add thermal mass, as well as to use up everything I can from a demolished brick wall I was given. I’m going to fill a void between the inner and outer layers with insulation board.

My experience so far has been a bit different to what the world of oven builders has been telling me. One commonly held belief is that insulation like ceramic blanket or rockwool or ceramic board will ‘reflect’ heat back into the structure. While this is possible, there needs to be an outer layer of brick or thick mortar wrapping up the blanket in addition to the blanket itself for any reflection effect to occur. The blanket will eventually dissipate its stored heat in both directions - back in and out. If you wrap your blanket in brick on both sides, the blanket still fills with heat, but it slowly dissipates the stored heat back into thermal mass surrounding it. If you don’t wrap your insular material in thermal mass, you will ultimately allow 50% of the stored heat run out into the atmosphere. In addition, your insular material will actually be absorbing heat from the bricks next to it, contributing to a slower heat up of the oven itself. I learned this with Bertha 2, which took over 18 hours to heat from cold, and really only started to get useful after the second bake for the week. Needless to say, once I figured out our insulation mistake, I got to pull her apart and replace the insulation with brick, and this sped her heating time up by many hours.

The advantage of brick is that while it absorbs heat, it also reflects heat. If you sit beside a brick wall in the sun, you will experience how brick reflects heat. When it becomes ‘soaked’ with heat, it then becomes a heat source - it actually ‘radiates’. So you get reflection, absorption and dissipation (radiation) of heat, in that order. Brick, as a material to work with storing heat, becomes more efficient over time.

One uses ones loaf to make a decent loaf. Or so they say…

So far I’ve used the oven for my standard bakes, and have kept the oven warm over multiple days doing various tasks - slow roasting on one day and baking pizza on another. Luna can hold baking temperature without fire for a couple of hours at the moment. In fact, the top decks increase in temperature for the first six hours of firing, and continue to increase without fire for the next three hours. On some nights I have finished the bake and checked the baking chambers about 10 hours later, and they still held over 120 C. I think I can improve on this by a significant amount by just beefing up the thermal mass and adding strategic insulation in some places.

I’ve done the big stuff, now I will do the little things. Watch this space.

If you would like to experience Luna first hand, I run workshops for the general public each month. Professional baking workshops are held four times a year. Check out what’s on offer.

Post script:

Just a little update regarding Luna’s thermal performance. Since writing this article, I’ve filled in all the besser bricks with rubble, bits of brick and crusher dust. I’ve also enclosed a sleeve of air surrounding the baking chambers with brick. I’ve bagged the outer shell with mortar, and I’m half way through adding a layer of bottles covered in mortar over the top. Once this is done, I’ll paint the top section in black bituminous paint. At this point, the oven holds an average 100 degrees C some 12 hours after a full bake of about 80 or so loaves. It takes just a bit less than 3 hours to reach baking temperature from cold, though if I really want the oven to be fully ‘soaked’, I’ll pre heat for about 5 hours. I’m yet to gather data on how long the oven takes to heat from 100 degrees, but I think it should re heat in just a couple of hours. All the little bits I’ve done to make it hold heat longer are making a difference; and I can see I’ll be doing more as the need to use the oven more often grows with demand for bread. I’m also noticing that to heat the oven takes less fuel now. This is a bit unscientific, because I’m using different wood from around the farm, but the effect is still noticeable. I still don’t have enough demand to fill 2 days baking, but this will gradually build as I get out and gather more subscribers.